Tessa Hadley: “I’m looking at the rhythm of why people do what they do, and why they might suddenly take a leap into risk”

The author of The Past is back with one of her best books yet

Tessa Hadley is the worst-kept secret in literary fiction. Hang around the new and recommended section of a bookshop for longer than a few minutes following a Hadley release and you’d be hard-pressed not to see someone add her to their pile. In the absence of murder or magic (though there is a spot of sex, drugs and communism in her latest book), her stories deal primarily in the every day of British middle class life: bereavement, adultery, gin-addled dinner parties. Begin to believe you’re on familiar terrain, though, and she’ll yank the Laura Ashley rug right out from under you. Because if her novels are consistently good, they’re just as consistently shattering.

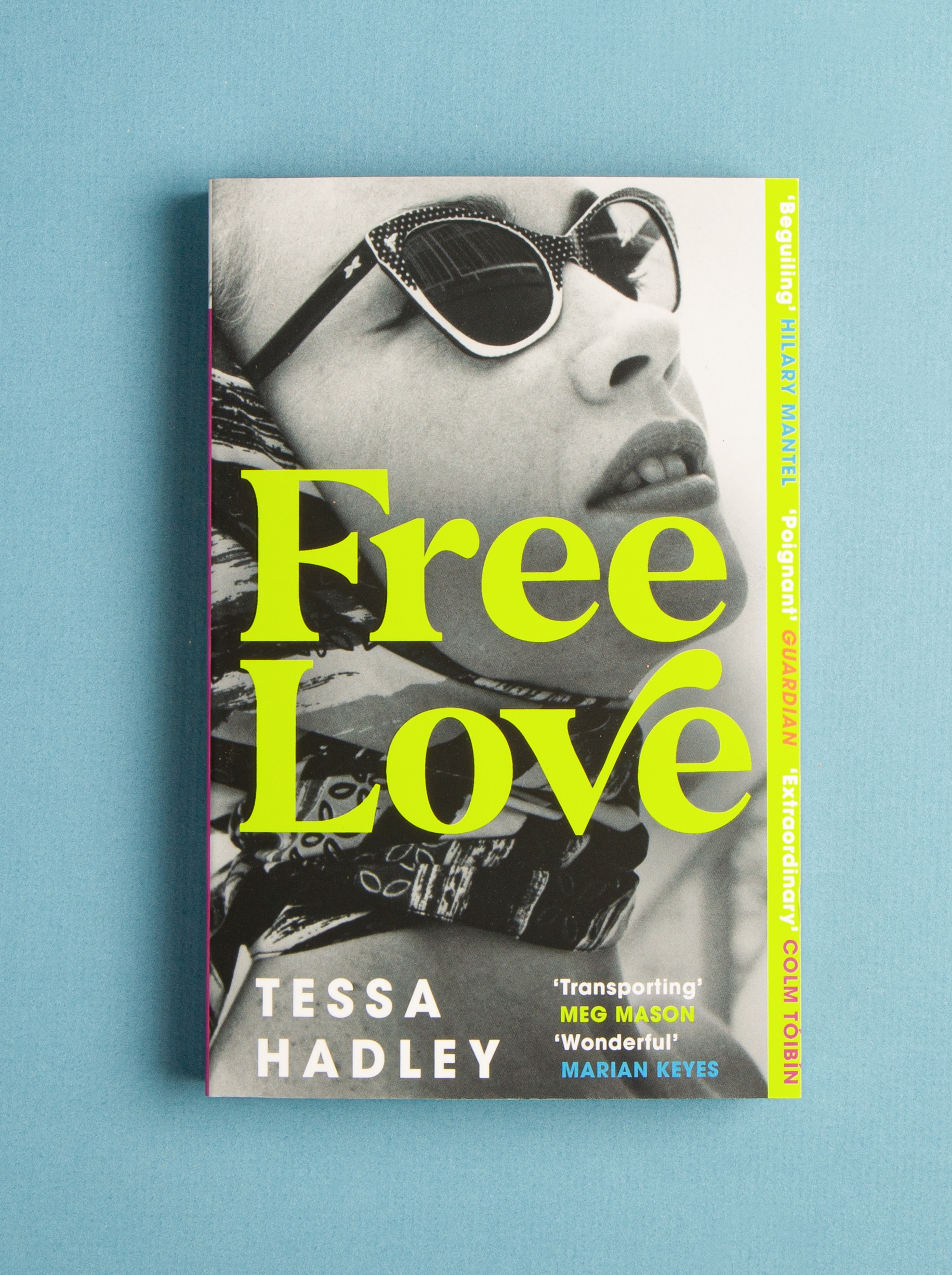

Hadley’s latest novel, Free Love, follows in the same tradition. Set over the course of a year, beginning in the annus mirabilis that was 1967, Free Love centres on Phyllis Fischer, a housewife in her forties who leaves the cloistered comfort of her suburban family home to embark on an affair with the twenty-something son of a family friend. The novel seesaws between two markedly different postcodes: the manicured Thames Valley suburbia of the family Phyllis has left behind, and the countercultural chaos of Ladbroke Grove in the 60s. It’s typical Hadley that one is as absorbing as the other.

“We live in the after effects of that period”

The revolution that’s unspooling outside – the underground press, the Grosvenor Square protests, the passing of the Abortion Act – is told through Phyllis’ own revolution; the abrupt realisation that “in her old life she’d only been half alive”. But don’t for a second think Hadley isn’t hyper aware that ‘free love’ presented a very different reality for women than it did for men.

“The thing that’s interesting to me is that those women who rebelled in the 60s and 70s, who divorced their husbands and left home in pursuit of some wonderful otherness, well, there’s another day and then another and then there’s more children and life goes on,” she tells me.

“Of course, I think we’re more disenchanted now. They were our mothers and grandmothers and we lived watching how they grabbed at the dream of another way of living – how it played out and became ordinary and daily. We live in the after effects [of that period] and are the beneficiaries of its freedom.”

Hadley, who was born in 1956 and came of age in the 70s, recalls how in her own youth, “Revolutionary, radical men were so dismissive of feminism. Would say it’s a side issue; it’s a distraction from the real class war and all of that. Make the tea.”

And yet, Free Love isn’t the clear-cut tale of a feminist heroine fleeing convention that you might think it is. Like many of Hadley’s characters, Phyllis is partial to a contradiction. No longer is she an apolitical housewife who doesn’t give a second thought to her husband’s job at the Foreign Office, but nor is she particularly politically strident in her new life either. If she’s anything at all beyond commendably brave, she’s probably just there for the fun of it.

What makes Hadley a feminist writer, then, is her refusal to pass judgement on her female characters. In fact, she refuses to pass judgement on any of them, but it’s always the women who seem to have the dreaded accusation of [gasp] unlikeability lodged against them.

Free Love is Hadley's eighth novel.

“I’m looking at the rhythm of why people do what they do”

“I’m not excusing her,” Hadley is quick to point out when speaking of Phyllis’ grief over her young son Hugh being sent away to boarding school against her wishes. “But I’m looking at the rhythm of why people do what they do and why they might suddenly take a leap into risk and jeopardise everything and nearly lose everything, but maybe get something back in return.”

She almost makes it look easy. Does the writing get any easier with time? “No, it absolutely doesn’t,” she counters with a smile in her voice. “Each [novel] creates a new question that you have to work out.” (Free Love is her eighth.) “But there does come the sense that you have readers with you, and that they think what you’ve done so far is okay. That builds some kind of confidence behind you and that makes confronting the problem of each novel less anguishing. Though there’s still some anguish along the way…”

Hadley, who didn’t publish her first book until the age of 46, is well-versed in the frustrations of failing to write the story that you want to. After studying English at the University of Cambridge, she met her future husband Eric Hadley at teacher training college and they married and had children young. She began to write in the latter half of her twenties, producing four or so novels that have since been confined to landfill.

Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Anne Enright are among Hadley's admirers.

“I can’t tell you what happens in your forties when you think, ‘I know who I am’"

“It really felt like I was doing the wrong thing with those books,” she says now. “I feel as if I was very much trying to write other people’s books. For a long time, I was impressionable rather than forceful. I just worshipped the writers I loved.” (Reading, she says, and “talking about books” is still her greatest pleasure.) “I can’t even tell you what happens in your forties when suddenly you think, ‘I know who I am. I know what I sound like.’ I’m just this, you know, mother and daughter and person living in this world. And that what I have to write about.”

She pauses before setting herself right: “No, that’s not quite how I want to put it. You know, the mysteries that you want to write about? I have to find my way to those mysteries through this material that’s close to hand. I guess that’s what I’ve found.”

If she ever had any doubt about whether she pulls it off, a quick glance at any one of her book jackets should assuage it. Hadley counts Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Anne Enright, Elizabeth Day and Colm Tóibín among her admirers. The late Hilary Mantel called Free Love “beguiling”. Critics have largely lauded her latest book (and the seven before). She is, in all her mastery of the craft, a writer’s writer.

So what’s her secret? “You should never complicate things for the sake of it,” she says – good advice, on all counts, for life. Thank God her characters don’t adhere to it.

Free Love by Tessa Hadley is published by Jonathan Cape and is now available in paperback.

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Kate McCusker is a freelance writer at Marie Claire UK, having joined the team in 2019. She studied fashion journalism at Central Saint Martins, and her byline has also appeared in Dezeen, British Vogue, The Times and woman&home. In no particular order, her big loves are: design, good fiction, bad reality shows and the risible interiors of celebrity houses.

-

How are Trump’s tariffs affecting the fashion industry?

How are Trump’s tariffs affecting the fashion industry?The fluctuating situation in the US is having very real consequences

By Rebecca Jane Hill

-

Here's every character returning for You season 5 - and what it might mean for Joe Goldberg's ending

Here's every character returning for You season 5 - and what it might mean for Joe Goldberg's endingBy Iris Goldsztajn

-

Celine's new Selfridges pop-up is an ode to summers on the French Riviera

Celine's new Selfridges pop-up is an ode to summers on the French RivieraA one-stop-shop for the ultimate holiday wardrobe

By Clementina Jackson