Work, life and dating in an ISIS war zone

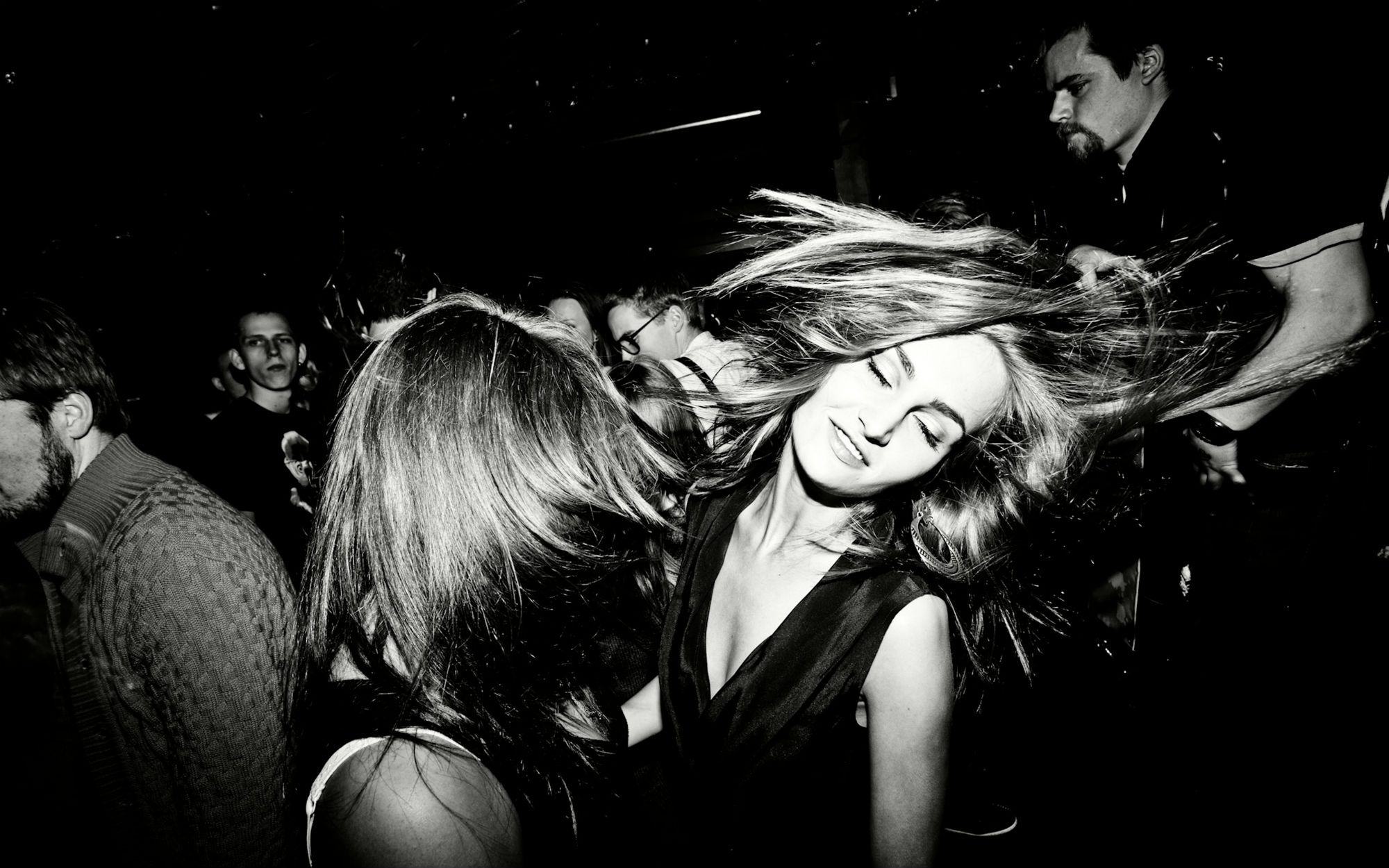

For many young charity workers and journalists posted to cover the war in Mosul there’s only one way to switch off from the horrors of their day jobs. Corinne Redfern spends a night on the town in Iraq

For many young charity workers and journalists posted to cover the war in Mosul there’s only one way to switch off from the horrors of their day jobs. Corinne Redfern spends a night on the town in Iraq

It’s a Thursday night in Erbil, and I’m being taken on a bar crawl. Or at least, I was supposed to be, but there’s a Kurdish soldier in the way. ‘Your name’s not on the list,’ he says, frowning at my provisional driving licence. I open my mouth to protest – talking my way into things is a CV-listed strength. I once made it into an NME Awards after-party by pretending to be Pixie Lott’s mum. Then I spot the guy’s gun. The bouncers at the after-party didn’t have guns.

A friend takes over. He’d put my name down three days ago, he says – well ahead of the 48-hour guest list cut-off. As they switch between languages; English, Arabic and Kurdish merging to form one convincing argument for why I don’t pose a danger, I spot the photographer I’m working with being frisked, intimately. ‘Any bombs on you?’ we’re asked, without irony. Twenty minutes of animated phone calls later, and we’re through to the next round of a rigorous four-step security check that will eventually see us arrive, retying our shoelaces and slightly dishevelled, at Erbil’s United Nations bar. The first thing I see walking through the door is someone passed out, head down on the pool table. It’s only 8pm.

Located in the north-west quadrant of Iraqi-Kurdistan, Erbil is three and a half hours’ drive from the Syrian border town of Faysh Khabur, and 50 miles from Mosul – at the time of writing, one of the last remaining ISIS strongholds in Iraq. But while the conflict has forced over 3 million Iraqi residents from their homes since 2014, and the Islamic caliphate continues to impose its regime of terror across the region, Erbil (or Irbil) has remained largely unscathed. Here, sustaining peace is the order of the day – and alcohol-fuelled escapism provides the scene of the night. Aid workers import suitcases full of Mexican tequila, ‘lagoon bars’ are positioned on top of swimming pools and guns can make it past security – albeit luminescent yellow plastic ones filled with vodka and fired into the mouths of thirsty expats. With a constant torrent of humanitarian aid workers, journalists, oil moguls and security services pouring in from all over the world, the city resembles a slightly dustier Dubai, filled with stressed-out adults determined to drink each other under the table to forget the day's traumatic events.

Dr Jacqui Wilmshurst, a psychologist who has worked extensively with aid workers and journalists who operate in war zones such as Afghanistan and Pakistan, says this behaviour is not unusual. ‘What I’ve seen in my clients is that when people live in a highly stressful or traumatic environment that requires them to be “on” at all times, then in the long term that adrenaline can become addictive, and lead them to seek it in other ways when they’re not working, too. That’s one reason why a lot of expats in war zones may have more sex – or perhaps cheat on their partners. The thrill sustains them,’ she says. ‘These behaviours can become exaggerated and accepted when you’re with like-minded individuals for sustained periods of time – such as coping with a day on the front line by passing around a bottle of whisky, or having sex as a means of getting some physical contact when, really, all you might need in that situation is a hug.’

It’s something I see on a regular basis in and around Erbil and, speaking to 20- to 30-year-olds I meet here, reflects how many people feel. ‘It sounds really ignorant in retrospect, but when I accepted my first internship out here, I just figured I’d have to stick to a curfew, cover up and be very careful all the time,’ says Sara*, 27, from the US. ‘To be honest, I was terrified.’ The only stories she’d ever seen about the Middle East had been bleak (‘and beige – just dust and khaki everywhere, you know?’), so to find herself in a city of gleaming new bar launches and apparently limitless alcohol left her feeling confused – and a little misled. ‘I’ve been here for five years, but when I post pictures on Instagram of state-of-the-art DJ booths, my friends are still like, “Hold on, where are you again?” They can’t reconcile the Iraq war zone they see on the news with the reality of my day-to-day.’

The truth is, she says, security might be tighter, but the nightlife here is wilder than anything she’d ever experienced back at home in the States; and it needs to be to help its inhabitants unwind from the extreme stress they face. ‘There’s a lot of drama, and I’d say there is always at least one person unconscious next to an empty vodka bottle at midnight,’ she says. ‘You’re not drinking to forget, exactly, but you are drinking to distance yourself from what you’ve been doing that day. If you spend 18 hours a day, six days a week working with rape victims or children who have been used as human shields by ISIS, then you really need to find a way to decompress and socialise for a few hours on your one night off. Otherwise you’d just be on your own in your room, far away from home, with all your thoughts.’

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

She’s not exaggerating: I catch up with Jess*, a 28-year-old producer from Canada, at Divan Erbil hotel’s no-expense-spared Cinco De Mayo-theme party. Think commissioned firework displays, discarded piles of Louboutins, breakdancers and DJ sets. ‘I spent all day today at a Yazidi women’s refugee camp less than 500 metres away from this place,’ she says, explaining that most of the women she’s been speaking to have experienced extreme trauma and kidnap at the hands of ISIS before escaping. ‘Then I come here, put my glow sticks on and everyone gets a little crazy. It’s about compartmentalising. Actually, you should meet my friend – he just got back from the front line in Mosul a couple of hours ago. His stories are some of the most harrowing that I’ve ever heard.’

Freelance journalist Jamie*, 27, from London, widens her eyes in agreement when I ask her about the city’s drinking culture. ‘The NGOs out here put their staff in shared houses – maybe six or seven employees living together at one time. So you might be in your twenties or thirties, but suddenly it’s like university all over again.’ The ensuing parties are legendary, she adds. Once, employees used their savings to hire Iraq’s famous cellist to sit on the rooftop and play for their barbecue while the guests drank vodka Martinis and beer, singing and swaying so hard they fell over.’

The best gatherings are held by French NGO employees,’ she recalls, although she is quick to note that party nights are funded by their own salaries, not the NGOs themselves. ‘As soon as you hear the French are having a house party, you cancel all your plans. They’re dealing with the worst atrocities of the war on a daily basis, so I think they party hard to cope with it. All day they are seeing babies who have had limbs blown off in air strikes; teenage girls who have bled out from sniper bullets… everyone has lost friends on the front line, but those guys see the absolute worst of everything.’ Jess nods at the mention of the French, but believes UK staffers could show them a thing or two. ‘I was at a British-run party last week and I can’t even tell you what went down,’ she says. ‘I hate to think what they were trying to forget.’

Colleagues are working in such a stressful environment, they need to trust each other and develop close relationships very quickly, explains Chiara Burzio, 36, Médecins Sans Frontières’ medical co-ordinator in Erbil. ‘Your colleagues are often the only people who understand what you’re going through, so you need to be able to offload with them in an environment outside of work. I’ve honestly never seen people drinking in an unhealthy way – there is so much psychological support provided to ensure everyone finds a healthy way to deal with life here. But I would definitely say that people smoke more.’

Even viewed through a haze of shisha and nicotine, the conflict’s proximity is inescapable – even if you’re simply seeking a caffeine hit. After arranging to meet friends at Barista – a Shoreditch-style coffee shop, complete with iced Americanos served in mason jars – I wander the length of the Christian district of Ankawa five times before eventually tracking my destination down for a meeting, only to discover that the building was recently relocated following an ISIS car bomb outside that killed four people and injured eight. Emergency preparedness officer Lottie*, 35, from the UK, says a lack of security is something you learn to live with in a war zone. ‘Every so often, you hear about a guy getting wasted and firing a round of bullets at the ceiling of a club somewhere. Stories like that stop being surprising after a while.’

Dating is also different when ISIS is just down the road. The constant comings-and-goings of an expat community built on month-long missions and 30-day visas lends sex a particularly casual air; Lottie tells me it’s an accepted fact that most of the guys she works with have ‘field girlfriends’ and ‘home girlfriends’. ‘The first question I ask on a date is “How are things?” The second one is “Are you actually single?”’ Her friend, Lucy*, 28, an English teacher from America, nods in agreement. But both women are keen to emphasise that it’s not just the men who sleep around. ‘People think we’d have bigger things to think about. And we do – I’ve been working in this industry for a long time, but the stories I hear coming out of Mosul are some of the worst I’ve ever come across. The things that ISIS is doing to women…’ Her voice trails off. ‘But when you’re miles away from your family and friends and hearing stories like that, you really want to forge new relationships as quickly as possible.’

I experience this first-hand. ‘I’m heading to the bazaar to buy a bulletproof vest,’ one guy told me after exchanging a total of four messages on Tinder. ‘Want to meet me there?’ Later, one NGO employee makes a bid to recreate a Hollywood romcom by persuading the Divan Erbil hotel’s bar manager to let us on to the balcony of the 21st floor. I see a flash across the horizon, illuminating the dark city below. ‘Lightening?’ I ask. ‘Air strikes,’ he replies casually, before burying his face in my neck.

‘Friends at home can’t understand how we’re using dating apps in a war zone,’ says Lottie. ‘But it’s only when I see everyone coupling up at house parties and disappearing into bedrooms like teenagers that I wonder if we should have grown out of this by now.’ Perhaps people who choose careers in war zones are actually very similar? Wilmshurst agrees. ‘It’s easy to assume that the environment is making them use alcohol or drugs or sex as a means of escapism. But research suggests that people who opt for these careers are predisposed to “running away”. They’re often impatient, seek constant stimulus or develop itchy feet if they stay in one place for too long.’

Still, Lucy questions if she’d be behaving like this at home: ‘It’s not that the rules are different here, it’s just that there are so many during the day, that after dark it’s like there aren’t any at all.’

*Names have been changed

The leading destination for fashion, beauty, shopping and finger-on-the-pulse views on the latest issues. Marie Claire's travel content helps you delight in discovering new destinations around the globe, offering a unique – and sometimes unchartered – travel experience. From new hotel openings to the destinations tipped to take over our travel calendars, this iconic name has it covered.

-

Penn Badgley and Blake Lively kept their breakup a secret from the Gossip Girl cast and crew - here's what we know about their former relationship

Penn Badgley and Blake Lively kept their breakup a secret from the Gossip Girl cast and crew - here's what we know about their former relationshipBy Jenny Proudfoot

-

Spring has finally sprung - 6 best outdoor workouts that are totally free and boost both body and mind

Spring has finally sprung - 6 best outdoor workouts that are totally free and boost both body and mindSoak in the nature and boost Vitamin D *and* endorphins.

By Anna Bartter

-

This iconic rose perfume is a compliment magnet—it makes me feel ‘put together’ after just one spritz

This iconic rose perfume is a compliment magnet—it makes me feel ‘put together’ after just one spritzGrown-up and elegant, yet not at all dated.

By Denise Primbet