Inside India's School For Child Brides: 'I Don't Know My Husband's Name'

They plait each other’s hair and sleep with diaries under their pillows – but they’ve got husbands waiting for them at home. Corinne Redfern visits the project transforming young girls’ lives in Rajasthan...

They plait each other’s hair and sleep with diaries under their pillows – but they’ve got husbands waiting for them at home. Corinne Redfern visits the project transforming young girls’ lives in Rajasthan...

Dapu can’t remember her husband’s name. She knows that on their wedding day, she wore bracelets stacked up to her elbows, and necklaces one on top of the other. She knows her two older sisters got married at the same time, that their father paid for dresses for all three of them, and that they came with matching veils. She can’t recall, however, what she ate at the ceremony, or if she got to dance. And she isn’t certain if she cried. But if she did, she says, it wouldn’t have been from happiness. It would have been because she was very, very scared.

The ceremony took place five years ago, when Dapu was nine. Until that day, she’d spent most of her time playing outside her hut, or helping her sisters clean the room where all seven members of her family slept. When her grandfather arranged a union with a boy from another village, she didn’t understand what was happening. ‘I still don’t know anything about him,’ she tells me, avoiding eye contact. ‘I don’t like thinking about it.’ Half an hour before our interview, Dapu had been shrieking with laughter and dancing along to Macarena. Now she’s shrinking into herself. ‘Two years ago, when they were 13 and 14, my sisters were sent 200km away to live with their husbands,’ she explains. ‘That’s what normally happens. You marry when you’re young, then go to live with them later. I haven’t seen them since. I don’t think they’re pregnant yet. I worry about it.’

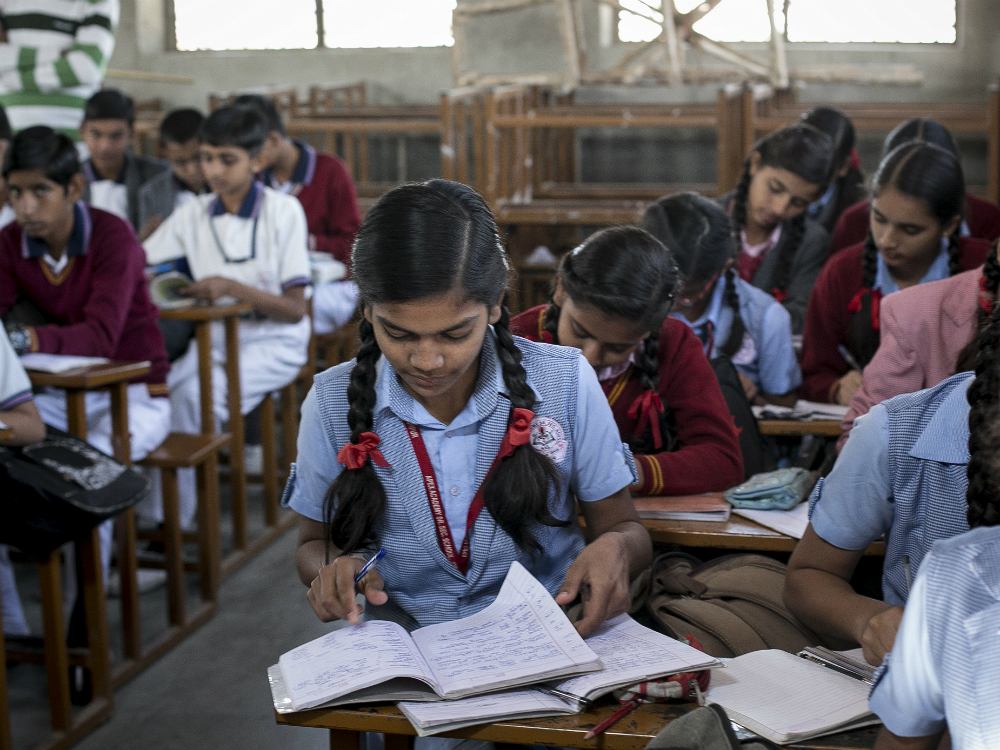

But Dapu’s fate might be very different. For the past four years, she has been living in Veerni Girls’ Hostel – a boarding house that accommodates 70 girls aged 10-17 and is currently working to eliminate child marriage in rural Rajasthan through education.

‘We initially founded the Veerni Project in 1993,’ explains Mahendra Sharma, who heads up the initiative. ‘We weren’t targeting child brides specifically, we just wanted to boost opportunities for women. We slowly developed relationships with the most deprived communities, and persuaded them to allow us to establish on-site literacy centres and sewing classes so that women would be able to earn their own income. But after ten years, we still weren’t getting the results we wanted. So in 2005, we found a site that we could transform into a boarding house, offering girls full-time schooling for free.’

Now with an in-house computer lab, weekly psychologist visits and quarterly medicals – plus access to two of the most exclusive (and expensive) mixed private schools in Jodhpur – the project’s success speaks for itself. In ten years, 99 girls have completed their exams – and 69 of them have gone on to higher education. Only one former child bride has ‘been returned’ to her husband, and she hit international headlines shortly afterwards for firmly insisting upon her right to a divorce. The others have all won scholarships to study at university, while their husbands wait at home. The hope is that by the time they graduate, they’ll be armed with the tools to escape the marriage altogether.

But while the programme may be comprehensive, it isn’t cheap. The average annual salary in India is £2,480, and Sharma calculates that it costs just over £1000 for each girl to live in the hostel for a year; money that’s raised through donations alone, and largely goes towards the cost of their education. At school they’re known as the ‘Veerni girls’, but teachers ensure there aren’t any problems about socialising with pupils from higher castes. And while parents who can afford it contribute 10 or 20 rupees (£1 or £2) a month in pocket money for their daughters, the project matches that for the other girls, so that they all receive the same. ‘They need that bit of independence,’ Sharma says. ‘Otherwise, what is the point?’

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

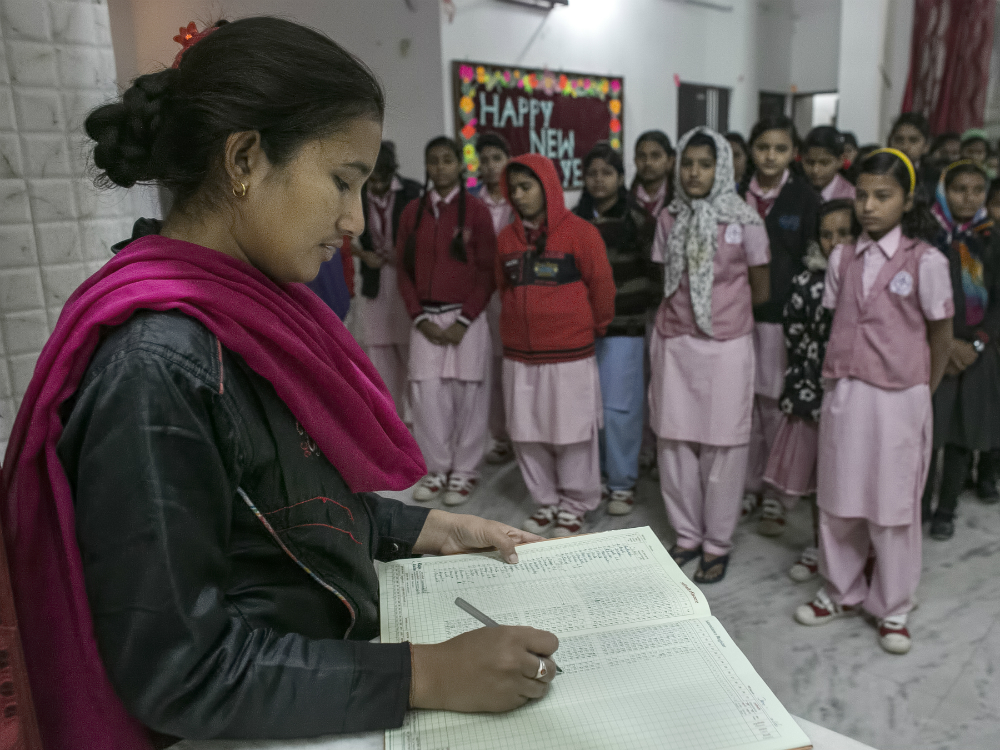

Nevertheless, everything else is carefully monitored. Attendance checks take place three times a day; ‘fruit time’ is scheduled in to ensure every girl eats at least one fresh apple every afternoon, and after taking the bus home from school, they file into the main hall, unroll a carpet and kneel on the floor to do their homework. Phones are banned, but a blind eye is turned to make-up (as long as it stays within the realms of kohl liner and nail polish). Carrier bags featuring photos of Bollywood celebs are carefully smoothed down and pressed between diary pages. Intricate henna – or mehndi – patterns are drawn on each other’s palms, with smiley faces on the fingertips. Families visit on the last Sunday of every month; weekly speakers give talks on female empowerment and there’s a talent show at Christmas. An ex-army officer has even been brought on board as the fitness instructor.

‘We want them to be children,’ explains Devshree, 22, who used to be a student at Veerni before she was hired as the hostel’s matron last year, helping the girls with their studies, and providing them with support, day and night. ‘I remember coming here when I was 14, and feeling really scared. I’d never spent a night away from home before.

I was lucky, because my father always understood the importance of education, but even though I was allowed to attend the literacy centre in my village, it wasn’t enough. Girls are not equal to boys in the villages. But when they come here, we try to show them that they are.’ Devshree doesn’t know it yet, but her father has been so impressed with her progress he’s promised the Veerni Project he won’t arrange a marriage for her unless she wants one. ‘She sends money home, but he doesn’t spend it,’ Sharma tells me. ‘He’s opened a bank account in her name, and deposits her wages there. She’s in control of her own future.’

One of the youngest girls in the house is Priyanka. Forced to marry a man from another village when she was five, she doesn’t think she knew what ‘marriage’ meant at the time. She’s not certain she does now. ‘Three of my sisters live with their husbands,’ she tells me. ‘My oldest sister is 18 and has three sons. One of them is five – I love playing with him.’ The 11-year-old now sleeps in the junior dormitory on the top floor of the hostel with 40 other girls under 14. Everyone has a bed with a foam mattress, covered in a pink, candy-striped sheet, and Priyanka wears a piece of string around her neck with the key to her suitcase – ‘for secrets,’ she whispers, conspiratorially.

Like Devshree, not all the girls are child brides. Monika came to the hostel when she was ten. Her father had been killed falling underneath a train three years previously, leaving her mother to work long hours packing peanuts on a nearby farm, and the then seven-year-old looking after her brothers and sisters. ‘When he died, there was nobody else to help,’ she says, quietly. When her mum heard about the Veerni Project, she begged them to take her daughter. ‘Now I have to work hard, so I can become a pilot,’ she explains. ‘My dad said being a pilot was the best job. I want to make him proud.’ She shares a room with Worship, 14, who joined the school after Sharma learned that her parents were so desperate for money, they were preparing to set her and her sister to work as prostitutes. ‘We had four spaces for this academic year,’ he explains. ‘Over 200 girls applied, so we had to pick the most urgent cases. For Worship and her sister, time was running out. She comes from the lowest caste, so her parents wouldn’t have been able to find them husbands, and they needed to find a way for them to earn their keep.’ It’s not clear whether the sisters know of their parents’ intentions. ‘My mother is illiterate,’ says Worship. ‘But now I am here, she is very supportive. She says if I can study hard, I can become an RAS officer [the Rajasthani equivalent of the civil service].’

You don’t need a before and after photo to see the positive impact of the project on the girls’ lives. But two months ago, its effect on the community as a whole became clear. Elders from Meghwalon Ki Dhani, a poverty-stricken hamlet located 80km into the desert – where every girl is married off before the age of nine – invited the Veerni staff members for a visit. Upon arrival, they were greeted with gifts; flower garlands and woven scarves for the women, red turbans for the men – symbols of the highest honour. A sound system had been hired, and a man wearing a striped shirt took to the stage with a microphone. There, he announced that the village elders had witnessed the project’s work and had made the decision as a community to not only outlaw child marriage, but to dissolve any unions that had yet to be consummated. For the first time, any ‘husbands’ who had a problem with their ‘wives’ leaving them wouldn’t be able to object – the girls had the entire community on their side.

When the Veerni staff offered to refund the village for the money they’d spent on organising the event, the elders refused. The staff pushed back, offering to build a modernised toilet block instead. The elders shook their heads, then – without any prompting – tentatively suggested building a computer centre in the village for the girls who were too young to attend the hostel so they could get a ‘head-start’. ‘Five years ago, that would have been their lowest priority,’ says Sharma, proudly. ‘They’re finally realising that girls aren’t just objects to be used or dismissed, and that by investing in their daughters’ futures, they’re investing in their own.’ For Dapu and her friends, it’s a revelation that’s long overdue. ‘Girls are actually way more intelligent than boys – we work harder and study more than them,’ she says. ‘And when we get an education, we’ll succeed more, too.’ If you’d like to support the Veerni Project or find out about volunteering in the hostel, visit veerni.com.

The leading destination for fashion, beauty, shopping and finger-on-the-pulse views on the latest issues. Marie Claire's travel content helps you delight in discovering new destinations around the globe, offering a unique – and sometimes unchartered – travel experience. From new hotel openings to the destinations tipped to take over our travel calendars, this iconic name has it covered.

-

I get lash lifts regularly—here’s how I combat 'lash dehydration’, as per expert advice

I get lash lifts regularly—here’s how I combat 'lash dehydration’, as per expert adviceHow I've got my flutter back on track...

By Rebecca Fearn

-

I tried Charlotte Tilbury’s bridal make-up service for my wedding, and *loved* it—here’s everything you need to know

I tried Charlotte Tilbury’s bridal make-up service for my wedding, and *loved* it—here’s everything you need to knowOne of my favourite beauty experiences to date

By Tori Crowther

-

Prince Harry's "proud" words about wife Meghan Markle are going viral

Prince Harry's "proud" words about wife Meghan Markle are going viralBy Jenny Proudfoot