#useyourvoice: 'I want to hear about Muslim women who are politicised without being labelled jihadi brides,' says author Sairish Hussain

Born and brought up in Bradford, Sairish has felt the dehumanisation of Muslims from the age of eight. Here she explains why she was compelled to write her debut novel and banish the devastating tropes of racism and radicalisation

Born and brought up in Bradford, Sairish has felt the dehumanisation of Muslims from the age of eight. Here she explains why she was compelled to write her debut novel and banish the devastating tropes of racism and radicalisation

Back in 2001 ‘circle time’ became a frequent part of our school life following the September 11 attacks. A teddy bear would be passed around the students and whoever it landed on would have to share something with the class: a thought, a comment, an opinion. In the weeks following the atrocity, our teachers decided that 9/11 would be the topic of discussion- over and over again. During one of these sessions (and with the class struggling to come up with new responses) the teacher rounded on a student and asked: ‘How would you feel, if your mum was in the tower?’

I remember the girl’s blank face. She floundered, in search of a word.

‘Sad,’ she eventually said, fingers clasped around the teddy.

‘Sad? Is that it?’ my teacher asked. ‘You’d be absolutely distraught.’

Bear in mind that this was Bradford, and the classroom was full of Pakistani Muslim kids. Bear in mind, that we were all around eight or nine years old.

I remember this so vividly because everything about this situation was wrong. I didn’t fully understand why at the time, but I felt it. The dust had barely settled, and across the Atlantic, teachers were asking children to imagine their parent’s dead. Not just dead, but as victims of the most horrific terrorist attack of recent times. How would you feel? Our loyalty was being questioned, our responses analysed and discarded as unsatisfactory. Sad? Is that it?

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Were the brown kids as troubled by the fiery wreck of those two skyscrapers as ‘normal’ children? What was going on in their homes? Whose side were they really on?

In my life, I categorise this as ‘the beginning’. It was a pre-warning of the intense global scrutiny we’d grow up under, something we would just have to get used to. Seeing brown people on TV became a cause for dismay because it never involved anything positive. The tabloids screamed at us; so did the six o’clock news. The limited representation we got in film, TV and books also became saturated with ‘war on terror’ content. Global discourse informed teenage me that Muslim men were monstrous beings. Women were oppressed and needed saving. The only time we appeared to be interesting or worth writing about was if we'd been forced into a marriage by our evil parents, or if we'd blown something up and caused mass murder. There was no in between.

For me, there was a slight problem in all of this, because most of the people that I loved belonged in this category. The Muslim one. It is an emotional issue for those of us who have family and friends that face constant dehumanisation. As an avid reader who found solace in books, I learnt that stories were largely at the root of this problem. Stories, whether delivered to us in a book or on TV, gave us the ability to relate to others and live for a while in their shoes. Hence, the solution could also be found within the types of stories that we chose to write.

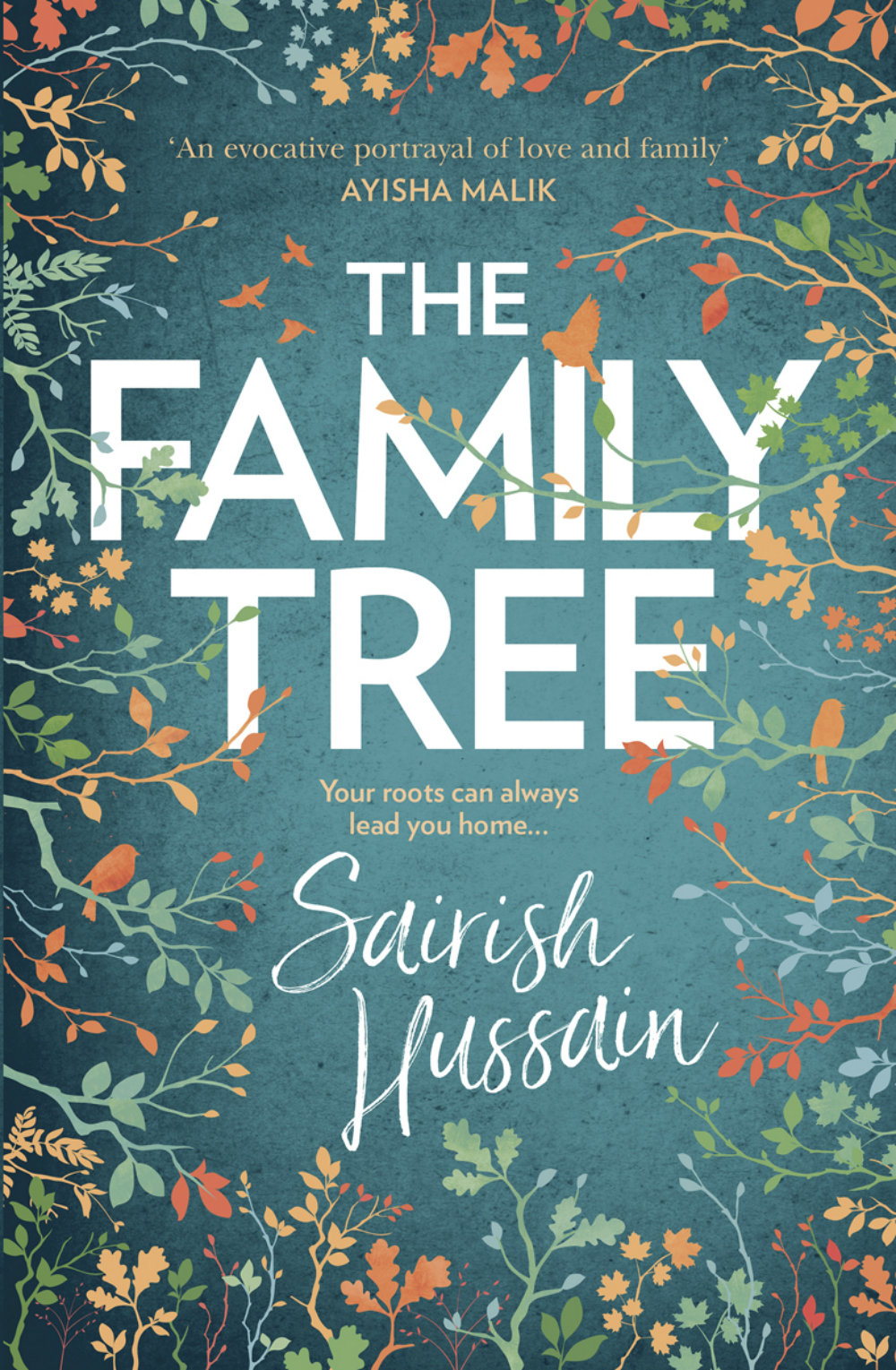

I began writing my first novel, The Family Tree, as a creative writing student at university, and I knew exactly what I wanted to achieve. I had no desire to write a ‘positive’ portrayal of British Muslims. No thanks. Similarly, I refused to write a story that screamed ‘LOOK HOW NORMAL WE ARE’! I wasn’t going to beg anyone to recognise my humanity. Instead, my main character, Amjad, is widowed in the first chapter and left with two small children to look after. Why? Because the primary concerns of people of colour on a day-to-day basis are not just racism, colonialism and radicalisation. Life happens to us too, though this has largely been ignored in artistic portrayals.

As recently as November 2019, a trailer debuted on Apple TV for a movie called Hala which drew controversy. The film, which is written by Minhal Baig and produced by Jada Pinkett Smith, shows an American Muslim teenager struggling with her Islamic faith and her parent’s expectations. In the trailer, Hala’s mother objects to her having a skateboard and she is seen finding solace in the arms of a white boy. Social media became flooded with negative responses as young Muslims expressed their disdain for the overused, tired tropes. Many asked: ‘can we please just have one normal movie?’

Of course, everyone’s ‘normal’ is different and the unfair burden placed on writers of colour leaves them susceptible to accusations of inauthenticity. The portrayal of people of colour in books often leads to higher expectations from readers who are crying out to be seen. Most writers do not wish to become spokespeople for their entire communities. Yet this can only be resolved if a range of stories are being told, which brings us to the publishing industry.

Book publishing feels notoriously closed off for many people. It is a London-centric, white, middle-class industry that struggles with regional, racial and social diversity. Plenty of research has gone into this, including the 2015 report Writing the Future: Black and Asian Writers and Publishers in the UK Marketplace by Danuta Kearn. The report included first-hand accounts of writers of colour who felt pigeon-holed and pressured into writing stereotypical stories. It is a great resource for those wanting to understand why literature by writers of colour has always been so homogenised and limited in scope. But more needs to be understood about this situation: the human side. The reality of what it actually looks like to grow up with your name attached to constant negativity.

We are not just the pathetic statistics that reflect the failures of the creative industries. We are kids made to feel guilty during a seemingly innocent class activity in primary school. Kids made to feel like outsiders at the age of eight. Quizzed and questioned about our opinion of a catastrophic event far beyond our emotional capabilities.

It is this frustration that compelled me to write my novel, The Family Tree. It is the story that I wanted to tell, a story that maybe teenage me might have liked to have read. Growing up, I wanted to hear about British Muslim women who could be angry and politicised without becoming jihadi brides. Women who did not need to become anglicised or secularised to be viewed as liberated. I wanted to read about young Muslim men who could frequent the mosque regularly without being radicalised. Academic, ambitious young men, who did not have to turn to criminality or terrorism to make their mark on society.

The desire to be seen as full, complex human beings is a valid one. Those with marginalised identities should see themselves reflected freely in books, and on our TV screens, and this should be normal.

* The Family Tree by Sairish Hussain (HQ, Harper Collins) is out now

The leading destination for fashion, beauty, shopping and finger-on-the-pulse views on the latest issues. Marie Claire's travel content helps you delight in discovering new destinations around the globe, offering a unique – and sometimes unchartered – travel experience. From new hotel openings to the destinations tipped to take over our travel calendars, this iconic name has it covered.

-

Penn Badgley and Blake Lively kept their breakup a secret from the Gossip Girl cast and crew - here's what we know about their former relationship

Penn Badgley and Blake Lively kept their breakup a secret from the Gossip Girl cast and crew - here's what we know about their former relationshipBy Jenny Proudfoot

-

Spring has finally sprung - 6 best outdoor workouts that are totally free and boost both body and mind

Spring has finally sprung - 6 best outdoor workouts that are totally free and boost both body and mindSoak in the nature and boost Vitamin D *and* endorphins.

By Anna Bartter

-

This iconic rose perfume is a compliment magnet—it makes me feel ‘put together’ after just one spritz

This iconic rose perfume is a compliment magnet—it makes me feel ‘put together’ after just one spritzGrown-up and elegant, yet not at all dated.

By Denise Primbet

-

‘If you’re using the #NotAllMen hashtag, you’re part of the problem’

‘If you’re using the #NotAllMen hashtag, you’re part of the problem’By Jenny Proudfoot

-

Munroe Bergdorf: 'Time's up on social media abuse'

Munroe Bergdorf: 'Time's up on social media abuse'Activist Munroe Bergdorf on why 2021 must be the year of lasting, impactful change online

By Sophie Goddard

-

After the Candice Brathwaite TV show storm: 'Are we finally ready to talk about colourism?'

After the Candice Brathwaite TV show storm: 'Are we finally ready to talk about colourism?'Ateh Jewel, Marie Claire's beauty columnist, talks about the Candice Brathwaite and Rochelle Humes docu debacle and why colourism - the preferential treatment of lighter-skinned individuals compared with darker-skinned Black people - must finally be acknowledged and action taken

By Ateh Jewel

-

'We cannot ignore the white privilege on display at last night's Capitol Hill riot'

'We cannot ignore the white privilege on display at last night's Capitol Hill riot'By Jenny Proudfoot

-

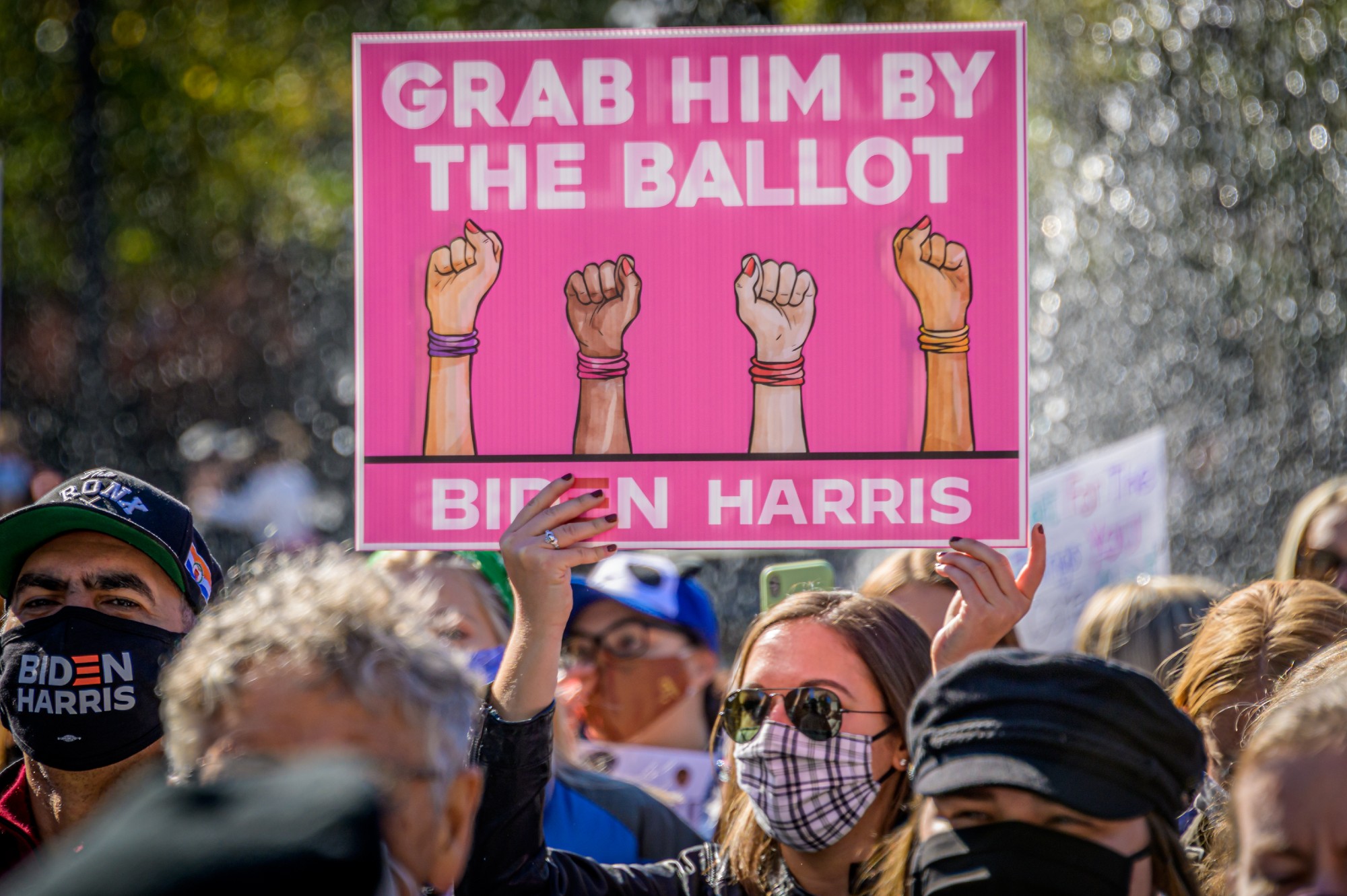

US Election 2020 - An Insider Tells All: ‘There’s no coming back from this, is there’

US Election 2020 - An Insider Tells All: ‘There’s no coming back from this, is there’Days before the most consequential election ever, Becca Andrews, a journalist at US news site Mother Jones, reveals what it's like living in Trump’s America and why, along with tens of millions, she’s holding her breath expecting the worst

By Marie Claire

-

Instagram turns 10: but is it breaking us or making us more human?

Instagram turns 10: but is it breaking us or making us more human?Happy birthday Instagram! A simple photo-sharing app was born on 6 October 2010 and changed the world for better or worse. Now home to more than a billion active users, author Daisy Buchanan examines her complicated relationship with it

By Maria Coole

-

'Why do we still have a problem with race?' asks anti-racism activist Layla F Saad

'Why do we still have a problem with race?' asks anti-racism activist Layla F SaadHow do you become a better anti-racist ally in 2020? For starters, recognise that if you're white and privileged, you're probably helping uphold an oppressive system. On Black History Month, we're shining a spotlight on what Layla. F Saad, author of Me and White Supremacy, has to say about shutting down racism

By Marie Claire

-

Hunger strikers demand justice for Breonna Taylor

Hunger strikers demand justice for Breonna TaylorBlack Lives Matter protests are still reverberating and now protesters in the US are on hunger strike seeking justice for Breonna Taylor, a woman killed at home by police in March. Marie Claire's Dami Abajingin asks why the killing of black women is rarely centre stage in narratives about police brutality and why #SayHerName matters

By Marie Claire