Exhausted and disheartened: a doctor on the NHS frontline speaks out

A 37-year-old consultant anaesthetist in central London (who has to remain anonymous) reveals exclusively to Marie Claire the truth about NHS working conditions and helping the sickest coronavirus patients

A 37-year-old consultant anaesthetist in central London (who has to remain anonymous) reveals exclusively to Marie Claire the truth about NHS working conditions and helping the sickest coronavirus patients

‘My job is currently unrecognisable. I used to arrive at work for 7.20am, change into scrubs and spend the day working in an orderly fashion through the list of patients requiring anaesthesia for surgery. At 6.30pm I’d finish my list of patients and head off home.

Now my main focus is looking after the very sickest coronavirus patients that arrive at hospital and need to go straight to intensive care. I put the patient to sleep, place a breathing tube and put them on a ventilator, stabilise them and take them to the ICU. Most patients are having a prolonged stay due to the problems with their lungs.

It’s the new normal, and that’s fine, but it happened incredibly quickly: we had a couple of days’ notice to flip from our normal routine into this heavy burden rota. I tend to now do two-day shifts - lasting 12 and a half hours - followed by two night shifts of the same time, and then I get two or three days off.

Doctors are dying and I'm really scared

Adding to the workload pressure is loss of staff: we have colleagues self-isolating because they have symptoms or one of their family members is unwell, and a percentage can’t come in to work the frontline for reasons such as pregnancy or underlying health issues. We are currently running about a 25 per cent staff absence rate.

The majority of patients now coming into the NHS are suspected of carrying coronavirus. The volume of patients Italy and Spain are dealing with seems unimaginable and terrifying. What’s more, healthcare staff have actually died in these countries, and now our own, which I’ll admit really scares me.

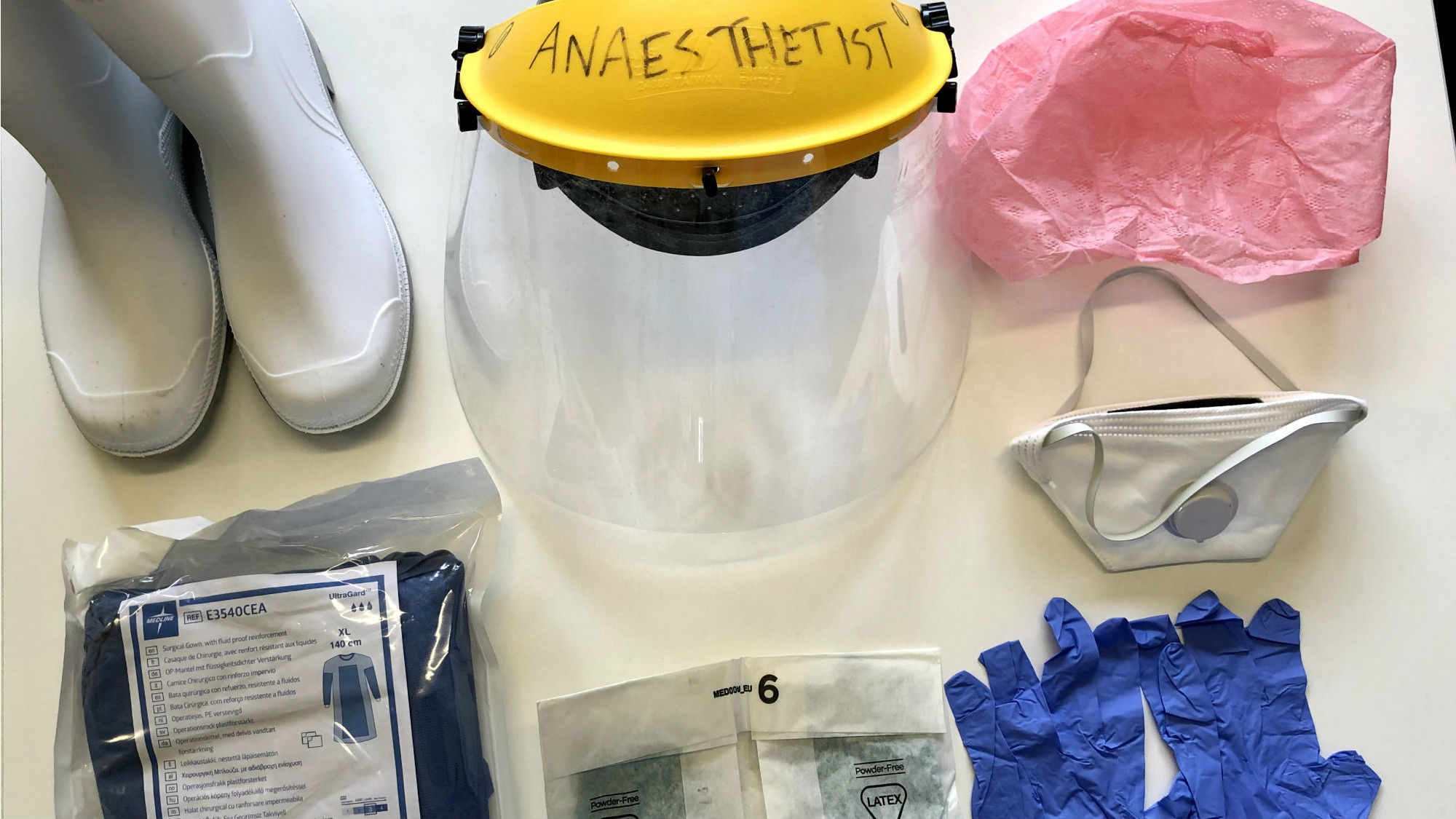

My new uniform is incredibly uncomfortable to wear. Of course, I’m grateful to be protected, but wearing scrubs, a long gown, wellies, a surgical mask, a visor, two pairs of gloves and an apron means you get incredibly hot, sweaty and dehydrated. The mask is so tight (I appreciate that’s the point) and it leaves marks over my face. Let’s just say I’m going to pay for a very nice facial after all of this to try and rescue my dry and sore skin.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

When it comes to protective equipment for the NHS, my hospital currently has what it needs, but how long it will last for I can’t answer. We had particular problems sourcing visors, which we ended up purchasing from a local DIY store ourselves. With the whole world wanting these items, every country is in equal need and none has priority.

The grim side of the NHS you never see

In my opinion, what NHS hospital staff really need as a priority are improved working environments now, and in the long run. It’s no secret that the majority of hospitals are not as modernised as we would aspire to have them. And the parts that patients don’t see have gone far beyond their useful working life.

From showers to rest areas, we are expected to exist in areas that are fatigued and often quite grim. We are all working incredibly hard and it would be great to take a much-needed break in areas that are nice – I’m not expecting David Lloyd style facilities, but money to update our environment would be a huge boost to morale.

After a shift I sometimes head to the supermarket, but it’s disheartening to arrive to empty shelves. I’m lucky to have a husband who can go out for me the majority of the time, and I also have neighbours who cook meals like spaghetti Bolognese and homemade soup to eat when I get home. Life would be a lot more challenging without these kindhearted people in my life. We have such a wonderful local community spirit.

By the time I’ve got home I’m exhausted, so although I do sleep, I always wake up early and can never switch off. One positive of the pandemic is people are opening up and feel able to talk about their emotions, for instance, admitting that they cried after a shift.

Why I burst into tears

On days off I sometimes walk in my local park, but I don’t always go out because I’m a risk factor and I want to reduce my contact with other people. I used to swim, but of course that’s not an option now, so I sit in the garden when the weather is kind and listen to podcasts. I normally read, but I’m not able to concentrate at the moment with all that is going on.

I’ve gone through various stages of emotion – denial, anger and sadness. I believe I’m in the acceptance stage now, although the uncertainty of the future is anxiety inducing and distressing. That said, I definitely feel valued by members of the public.

On March 26 my street first showed their gratitude to the NHS by applauding from their doorways. Beforehand I had said to my husband that we would rather have better funding or kit, but when I opened the door I burst into tears and found the ‘clapping for our carers’ moment incredibly emotional and overwhelming. I’m grateful to still be in work and being paid. It was lovely that people were clapping us when I know they have their own stresses, even if they are not working on the frontline.’

Olivia – who rebranded as Liv a few years ago – is a freelance digital writer at Marie Claire UK. She recently swapped guaranteed sunshine and a tax-free salary in Dubai for London’s constant cloud and overpriced public transport. During her time in the Middle East, Olivia worked for international titles including Cosmopolitan, HELLO! and Grazia. She transitioned from celebrity weekly magazine new! in London, where she worked as the publication’s Fitness & Food editor. Unsurprisingly, she likes fitness and food, and also enjoys hoarding beauty products and recycling.