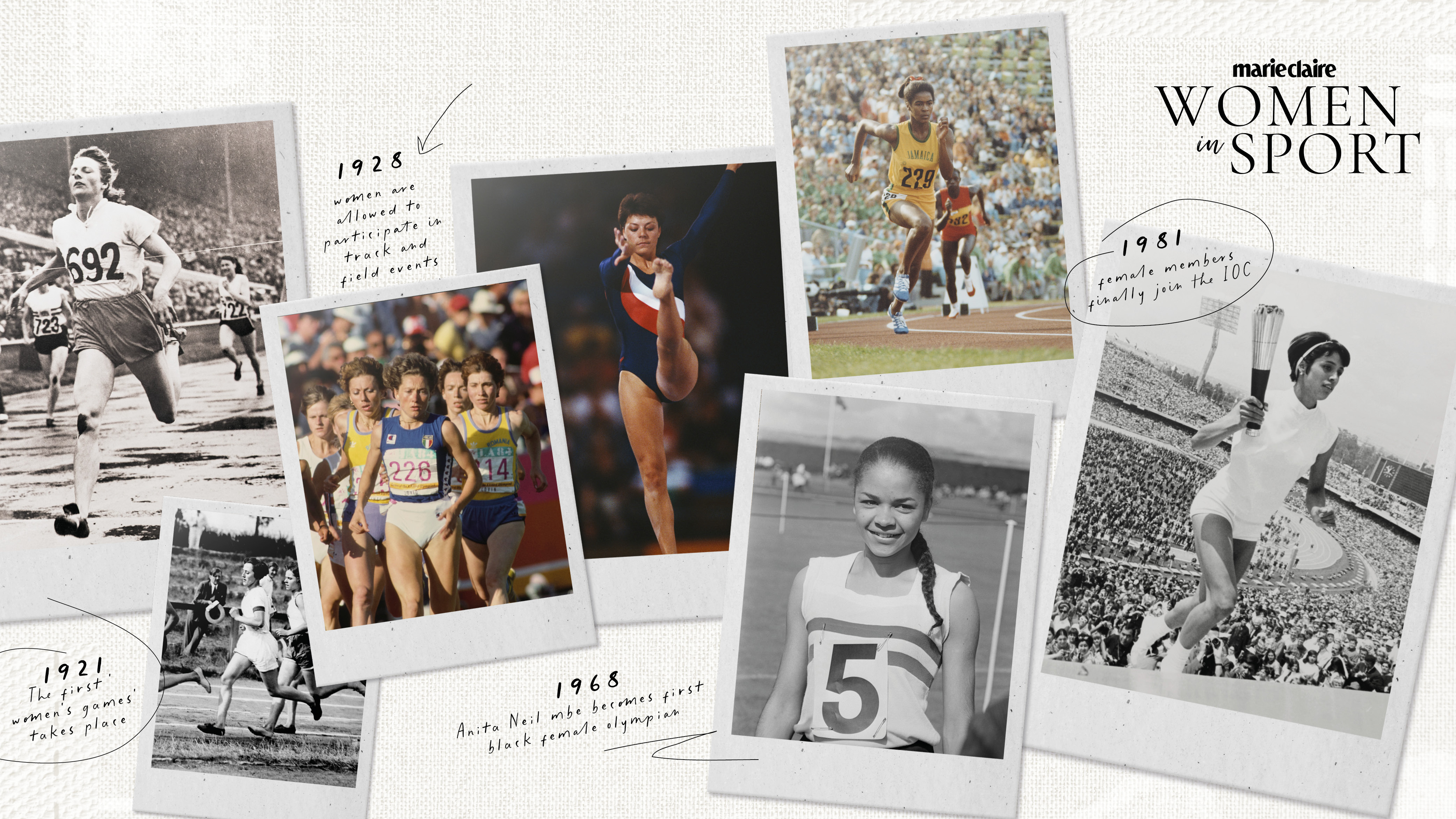

This year marks the first ever gender-equal Olympics – 14 milestones that highlight how far the Games have come

Inspiration at its finest.

The 2024 Paris Olympics is set to be the first to achieve full gender parity with an equal number of male and female athletes. But, where did the road to Olympic equality begin, and what still needs work?

There’s a game I like to play at low-key social events to get to know people a little better (and invigorate the conversation, if it’s feeling a tad laboured between new acquaintances). There are no real rules, nor is there a winner or a loser. The crux of it is I want to hear your dream festival line-up; five artists, dead or alive, performing at one glorious – possibly chaotic – event. Responses are telling of genre taste, yes, but also of the tender and touching moments people hold dear to them – memories associated with their chosen music. If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to play a similar game with you – but with a twist. I’d like you to list the five Olympians – currently competing, retired or no longer alive – you would love to watch at their peak, all together at a Games.

My list is easy to compile: Jessica Ennis-Hill, Kelly Holmes, Simone Biles, Laura Kenny, and Usain Bolt. For me – and I’m sure many other millennials, in particular – these athletes represent both colossal talent and warm nostalgia. Each one is associated with micro-milestones in my life – sun-drenched summer mornings tuning into the Games with my dad, and discovering, surprised, I actually do enjoy sport, as I fizz with excitement seeing Kelly zoom past a competitor. Without discrediting or dampening the successes of the Chris Hoys and Max Whitlocks – men I’ve enjoyed watching just as much – it’s the women’s wins and enduring trailblazing that are tattooed in my mind.

I, therefore, welcomed the news that the 2024 Paris Olympics is set to be the first ever gender-equal Games – a long overdue landmark, during which the same number of male and female athletes will be competing (48.7% of athletes at the Tokyo 2020 Games were female, making it the most gender-balanced Olympics until now). And that’s not all – this year’s Olympics will also mark the first time a women’s event (the marathon) concludes the Games, which is traditionally closed by the men’s marathon.

We’ve seen such monumental progression in women’s sport in recent years (Arsenal Women will play most of their 2024/25 WSL fixtures at Emirates Stadium for the first time, following record-breaking attendances during the 2023/24 season, as one example) and sometimes we need to take stock of how far we’ve come. The blunt reality is, if the rules from early modern Olympic Games applied today, most women would not be able to partake – including the four on my list, and possibly some from yours too. It’s hard to imagine a world in which athletes now symbolic of the Games would not have been allowed to compete – and yet, you may be surprised at how recently some restrictions were lifted. So, keep scrolling for your full run down. Of course, this piece is part of our Women in Sport summer special, so do check out our cover interview with Team GB sprinters Daryll Neita and Laviai Nielsen, not to mention 14 fun facts about the athletes that'll have you rooting for them come race day. For more long form reads, scroll our deep dives into the lack of research into female athletic performance and why mothers are underestimated in sport.

Olympics equality: a brief history of the Games

The modern Olympics was founded in 1894 (the first Games held in 1896) by French Baron Pierre de Coubertin. He believed that sport supported educational development and that a revival of the Olympics – involving countries worldwide - could help to promote international peace. He also believed that women had no place competing at the Games.

Of course, at the time, women had very few rights, and their primary purpose was to raise children and perform wifely duties. Competing at the Olympics, it was thought, would risk their ability to fulfil that purpose. “Coubertin was from a very conservative, aristocratic family,” explains Jörg Krieger, Associate Professor at Aarhus University researching women at the Olympic Games, and co-author of Women in the Olympics. “There's definitely a class issue that is important here. Additionally, there were medical concerns that there would be health risks to females participating in elite sport.” It was feared that women would suffer reproductive issues were they to exceed their "natural limitations" during physical activity, and that engaging in sport would result in increased masculinity. Whatever that means.

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Discussing the possibility of women competing in a letter from 1912, Coubertin wrote that it would be "impractical, uninteresting, ungainly and […] improper". Sadly, it was an opinion shared by many, and consequently, it would take a century from the time he penned those words for all sports to be accessible to female athletes at the Olympics.

The 1900 Games was not organised by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) – an organisation formed by Coubertin to support and monitor the organisation of the games, of which every member was male at the time – and Coubertin, therefore, didn’t have much influence. As a result, 22 female athletes participated in croquet, equestrian dressage, golf, sailing, and tennis at the Paris Olympics. Women made up 2.2% of all competitors. “These sports were considered to be appropriate for female athletes as they could wear long clothes, and their bodies wouldn't be on display as much,” says Krieger. They were thought to be less physically demanding activities, allowing women to remain "graceful" and "feminine" while competing.

So, what happened between then and now? Keep reading for 14 of the major milestones.

The road to Olympics equality – 14 surprising milestones highlighting how far the Games have come

1. 1921: The first ‘Women’s Games’ takes place

In 1921, after the IOC refused to allow female athletes to compete in track and field, the Women’s Olympiad took place in Monte Carlo.

In 1922, French feminist and rower Alice Milliat organised the first Women’s World Games to ensure female leadership in women’s sports. 75 women from five countries participated, and 20,000 spectators attended. Further Women’s World Games took place in 1926, 1930 and 1934.

Ther International Women's Sports Federation, which organised the Games, was dissolved following the 1934 competition, as women’s sports were increasingly integrated into the IOC and the International Association of Athletics (IAAF).

2. 1928. Women are allowed to participate in track and field events for the first time

Initially prohibited because it was considered uncouth and unsafe for women to engage in high intensity physical activities, in 1928 five track and field events were added to the programme for the first time: the 100m, the 4 x 100m relay, the high jump, the discus and the 800m. This decision was largely influenced by concern from the IOC over female leadership in women’s sport, and the success of Alice Milliat’s Women’s World Games. Female athletes set world records in all but the 100m at this Games.

Fanny Blanker-Koen of Holland becomes the first triple champion of the 14th Olympic Games, finishing third in the final of the women's 200-meters event.

3. 1928: Women are prohibited from running distances longer than 200m

Yes, you read that right. The same year that women’s athletics debuted at an Olympics Games, long distance running became prohibited.

It was reported that, after completing the 800m event in the 1928 Games, female athletes appeared totally exhausted. IOC leaders became concerned this indicated over-exertion, and that women’s bodies were too feeble to compete in such events. Women were not allowed to participate in the 800m for 32 years.

4. 1932: An Olympic Village was built for the first time… but women weren’t invited

Instead of being hosted in the first of its kind Olympic Village for the 1932 Los Angeles Games, like the men, female athletes were put up in a local hotel.

5. 1960: The 800m returns!

Following a (let’s be honest: unnecessary) 32-year-long wait, women are finally allowed to compete in the 800m once more at the 1960 Rome Olympics. It remained the longest discipline until 1972, when the 1,500m race was introduced for female athletes.

6. 1968: Anita Neil MBE becomes Team GB’s first Black female Olympian

At the 1968 Games in Mexico, sprinter Anita Neil MBE became Britain’s first Black female Olympian. She participated in the 100m and the 4 x 100m relay. She competed in the same events at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, also.

In an interview featured on the Team GB website, Neil says: “I knew I was the non-white person in the team but I did not think that much more about it.

“I was trying to blend in but to know that I am Britain’s first black female Olympian is fantastic. It is something I am really proud of.”

7. 1972: Women accounted for only 14.8% of Olympians

52 years ago, only 14.8% of Olympians at the 1972 Munich summer Games were women. In contrast, women constituted 28.9% of Olympians at the 1992 Barcelona Games.

Yvonne Saunders of Jamaica starts the quarter final heat 2 of the Women's 400 metres competition on 2nd September 1972 during the XX Summer Olympic Games at the Olympic Stadium in Munich, Germany.

8. 1981: Female members finally join the IOC

For 87 years, the IOC had been entirely made up of men. In 1981, two women – Pirjo Häggman of Finland and Flor Isava Fonseca of Venezuela – joined the committee and assumed roles in Olympic leadership for the first time.

9. 1984: Women are finally permitted to participate in the marathon

It was only 40 years ago that female athletes were allowed to compete in the marathon for the very first time at an Olympics. It was the fastest women’s marathon in history – nine athletes finished in under 2:30.

Several other events also became available to women at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, including artistic swimming, cycling, rhythmic gymnastics and shooting. The Heptathlon also replaced the pentathlon.

10. 1991: All new sports must include women’s events

About time. In 1991, the IOC introduced a new rule that requires any sport applying for Olympic involvement to include women’s events.

Diana Elliott of Great Britain clears the bar in the Women's High Jump competition during the XXIII Olympic Summer Games in 1984.

11. 1996: Women competed in beach volleyball for the first time… but were required to wear bikinis

Beach volleyball became an official sport at the Olympic Games in 1996 and, thanks to the 1991 rule requiring new sports to accommodate female athletes too, women could participate. However, women were prohibited from competing in anything that wasn’t a bikini or swimsuit. This meant that many, such as muslim women, could not partake, and it contributed to the sexualisation of female athletes.

Kit remains a point of contention today. Nike sparked global outrage when it released a sample of its official 2024 Olympic kit for Team USA earlier this year, which featured a racing vest and knee-length cycling shorts for the men, and an extremely high-cut unitard for the women. And yet, kit is a key factor in performance.

“For anything you do, whether you're on the track running or in an office, you have to feel good within yourself,” says Jeanette Kwakye MBE, former sprinter, Olympian and the broadcaster who will be leading morning BBC coverage at this year’s Games. The most important thing, she says, is that athletes have a choice, and that we don’t ostracise women based on their kit preferences.

12. 1999: Mandatory sex testing is abolished

Sex testing began in the 1930s and 1940s when the IAAF, which oversaw track and field, would randomly check the sex of female athletes they considered ‘suspicious’ (because of their appearance or athletic ability) via physical exam. In 1968, the IOC introduced mandatory sex testing, which 1972 Olympic pentathlon champion Mary Peters has previously said was “the most crude and degrading experience I have ever known in my life.”

Various methods of sex testing followed, including the Barr body test in 1967, which used chromosomes to determine sex, and hormone testing. Mandatory sex testing was finally abolished for Olympics participants in 1999. However, because international federations are responsible for eligibility rules, many intersex and trans athletes still face many challenges attempting to compete at the Olympics.

13. 2012: Women are allowed to compete in every sport on the Olympic programme

Although only 12 years ago, with the introduction of women’s boxing, the 2012 London Games was the first Olympics where women were granted permission to partake in every sport on the programme. Additionally, 2012 was the first year every participating country had female competitors.

Nicola Adams won gold in the Fly category – a moment many of us will recall – and, along with many other female athletes that year, made history. “It's a game changer, isn't it,” says Kwakye. “Because, all of a sudden, now you can see that there is a pathway. If you want to be a female boxer, you can go and do boxing.”

14. 2024: The IOC introduces an AI system to help protect athletes from online abuse at the Paris Olympics

Ofcom’s 2022 Online Nation report revealed that women are more likely to be negatively affected by online abuse than men. So, while the IOC’s new AI System is for all athletes, it’s a welcome step forward for women at the Games.

The technology will monitor thousands of social media accounts – across all major platforms – identifying and flagging threats, so that abuse can be dealt with as efficiently as possible. Some social media platforms, however, are notoriously terrible for responding to hate speech and disciplining perpetrating accounts, so it will be interesting to see how the AI system can assist.

Additionally, there will be a dedicated mental health helpline for all participants in the 2024 Paris Games, and it will remain accessible for four years.

What needs to happen next for Olympics equality?

While equal representation of men and women at the Games is a welcome step forward for gender parity, there’s still work to be done.

When I ask Krieger what he thinks of this year’s first ever gender-equal Olympics, he says he considers it a marketing campaign. “Questions about gender equality are being asked everywhere – we discuss them in every forum – so of course the IOC, together with the French organising committee, would try to promote the Olympics in this way.” That said, he also acknowledges that we’ve come very far from that first 1896 games, and that the IOC has played an instrumental role in the progress that has been made.

“But, for me, the way they are promoting it is too much because there are still issues. It’s like they are saying ‘this is gender equality, and we have finally reached it’. If we look, for example, at coaches, the percentages of female coaches versus male coaches is still significant. Now, we cannot influence this directly, but I think there's still a lot more to be done.” At the 2020 Tokyo Games, only 13% of coaches were women.

Additionally, he feels the IOC could further improve gender equality at the Olympics by supporting more girls at grassroots level and putting more women in leadership roles. “We’ve had 130 years of the IOC, but we have not had a woman as president of the IOC, for example. I'm not saying the next president should be a woman – it should be the best possible person – but I think that they should promote women to become the best person for the position.”

When Kwakye competed at the 2008 Olympics, she said the Games felt like a level playing field to her. However, discrepancies between sponsorships for the men and women presented female athletes with an additional challenge their teammates didn’t necessarily face. “Away from the Olympic Games, the men always got paid more,” she says. “They got bigger sponsorships. It was always the case. Even though I'd achieved a lot more than some of the men in my Great Britain team, I was getting paid significantly less, so that wasn't always fun.”

Kwakye is pleased with the progress we’re making in women’s sport as a whole, but says that in order to reach complete gender parity we need more male allies. “There are a lot of men in powerful places – that’s the backing that is needed,” she says. “We need those fantastic allies to come out and be like, ‘no, that's not acceptable’. They need to feel comfortable to call it out.”

The 2024 Paris Olympics is an important milestone for gender parity at the Games, yes, but it cannot be the final one.

Abbi Henderson is a freelance journalist and social media editor who covers health, fitness, women’s sport and lifestyle for titles including Women's Health and Stylist, among others.

With a desire to help make healthcare, exercise and sport more accessible to women, she writes about everything from the realities of seeking medical support as a woman to those of being a female athlete fighting for equality.

When she’s not working, she’s drinking tea, going on seaside walks, lifting weights, watching football, and probably cooking something pasta-based.

-

Prince Harry reportedly extended an 'olive branch' to Kate and William on latest UK trip

Prince Harry reportedly extended an 'olive branch' to Kate and William on latest UK tripBig if true

By Iris Goldsztajn

-

How Prime Video is protecting Blake Lively amid her new movie promo

How Prime Video is protecting Blake Lively amid her new movie promoAn understandable move

By Iris Goldsztajn

-

It's the must-have bit of fit kit of the year - a fitness expert shares their top 5 tips for choosing a walking pad

It's the must-have bit of fit kit of the year - a fitness expert shares their top 5 tips for choosing a walking padThis year's fitness must-buy.

By Katie Sims

-

Introducing Global phenomenon, Olympic medallist and rugby icon Ilona Maher

Introducing Global phenomenon, Olympic medallist and rugby icon Ilona MaherBy Ally Head

-

We asked a record-breaking athlete for her 10km training tips - trust us, you're almost guaranteed a new PB with this advice

We asked a record-breaking athlete for her 10km training tips - trust us, you're almost guaranteed a new PB with this adviceKeen to up your speed?

By Ally Head

-

As the Paralympics finishes, Livvy Breen chats following your dreams, owning your strengths, and never giving up

As the Paralympics finishes, Livvy Breen chats following your dreams, owning your strengths, and never giving upThe three-time Paralympian chats to MC UK.

By Ally Head

-

Lauren Steadman: "I use sport as a vehicle - I might have an arm missing, but I'm just as strong as you are."

Lauren Steadman: "I use sport as a vehicle - I might have an arm missing, but I'm just as strong as you are."The Paralympic champion and MBE owner discusses her most important life lessons.

By Ally Head

-

Charley Hull talks self care, confidence and the most pressing issues for female pro golfers today

Charley Hull talks self care, confidence and the most pressing issues for female pro golfers todayAs part of our Women in Sport special this summer, the British golf pro shares life lessons from her exciting career.

By Jenny Proudfoot

-

Jess Ennis Hill chats motherhood, menstrual cycles and investing in workout kit that makes you feel great

Jess Ennis Hill chats motherhood, menstrual cycles and investing in workout kit that makes you feel greatLife lessons from the three-time world champion.

By Ally Head

-

Emma Raducanu talks self care, bouncing back from injury and why there's more to life than tennis

Emma Raducanu talks self care, bouncing back from injury and why there's more to life than tennisAs part of our Women in Sport special this summer, the British tennis pro shares life lessons from her already triumphant career.

By Jenny Proudfoot

-

I trained like an Olympian – and have a newfound respect for their strength, agility, and motivation

I trained like an Olympian – and have a newfound respect for their strength, agility, and motivationBy Abbi Henderson