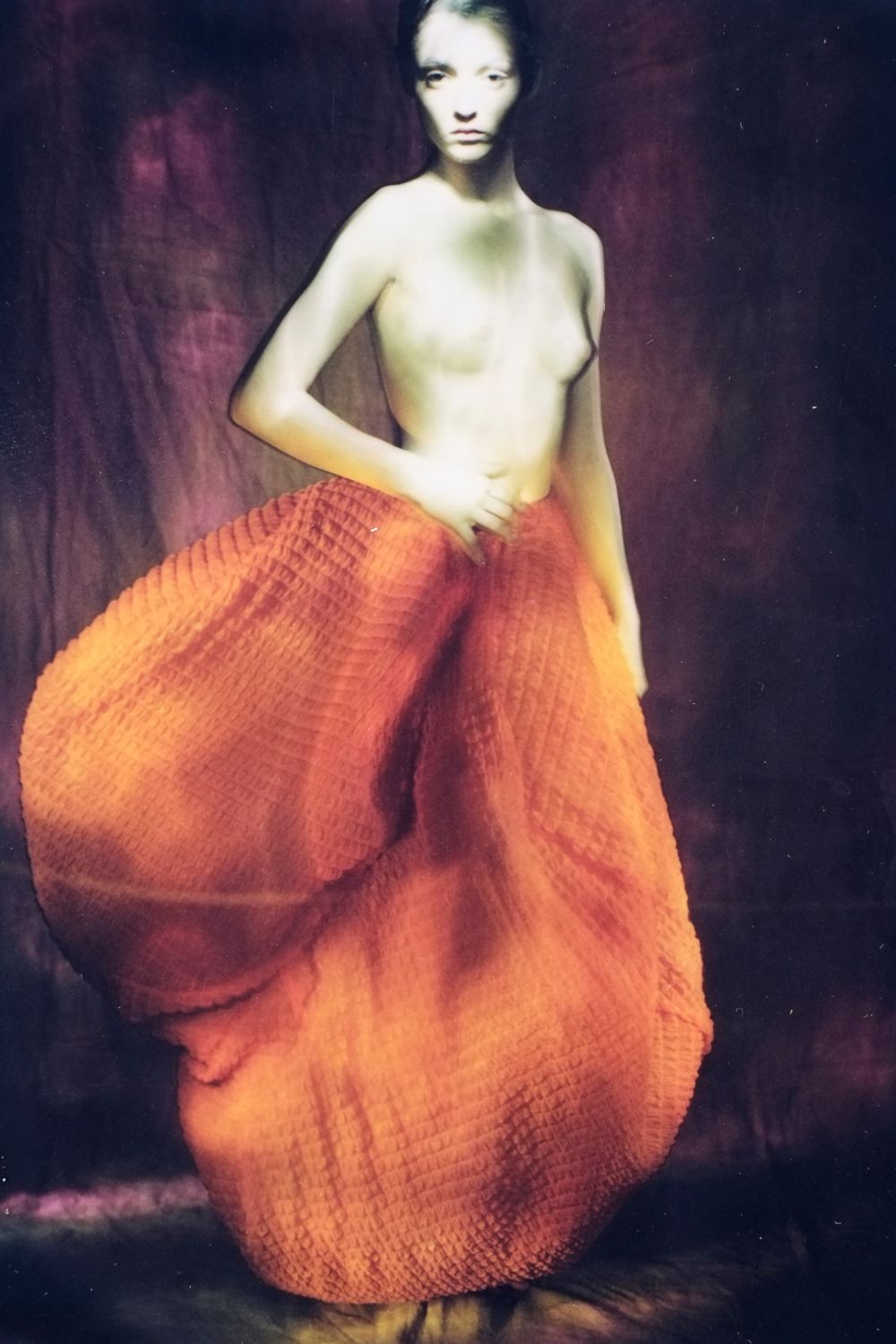

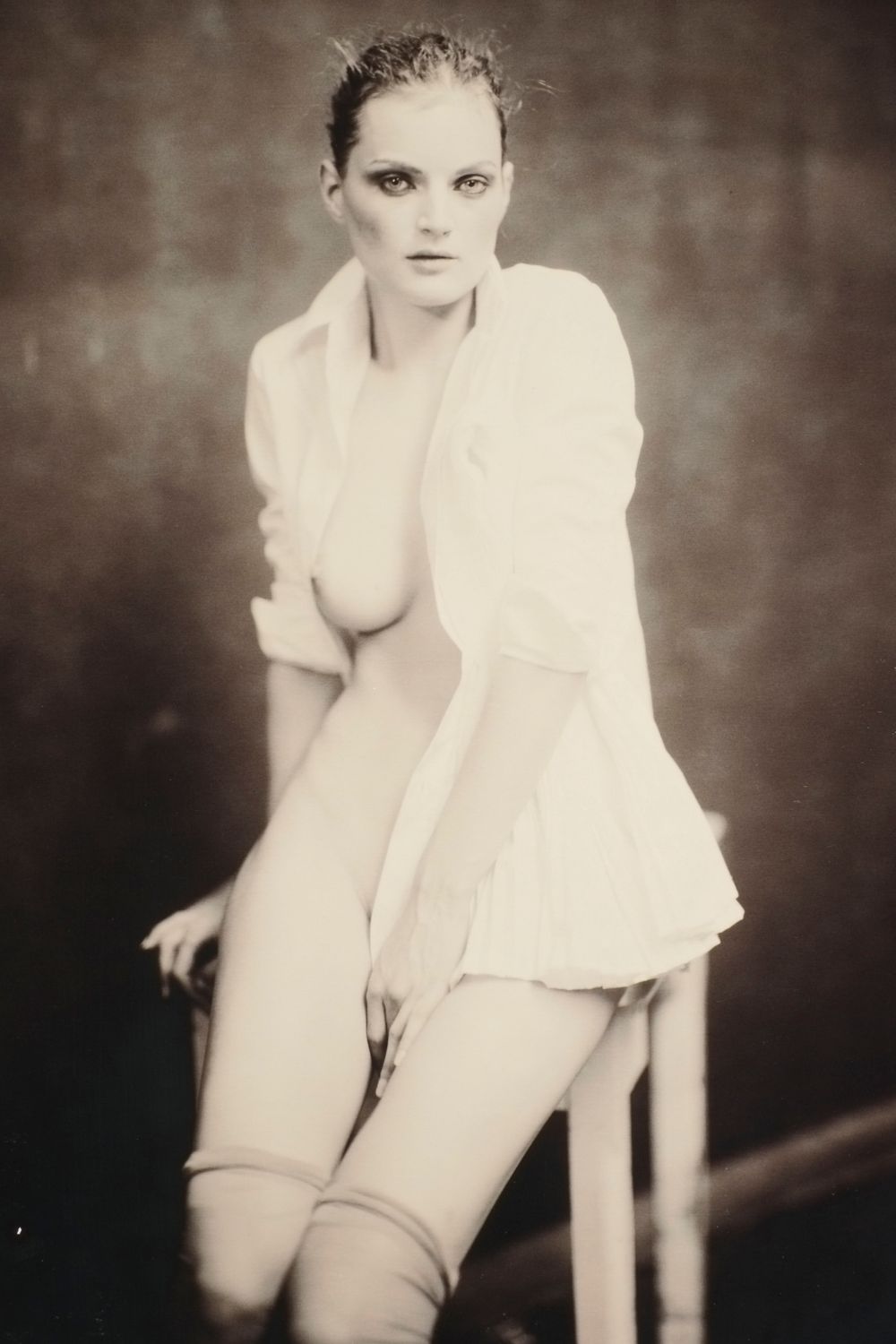

Ethereal young girls with messy chignons; strong, deep eyes… Paolo Roversi's women are undeniable. His images defy time, possessing the quality and aura of the early daguerreotypes and autochromes of the late 19th century while showcasing the greatest top models and the most cutting-edge fashion of the time. In his images, currently on display in a groundbreaking exhibition at the Palais Galliera, we see name after evocative name, face after iconic face: Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons, Galliano, Alaïa... Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Guinevere Van Seenus, Inès de la Fressange, Natalia Vodianova... All of them have passed through the mythical Studio Luce, in the 14th arrondissement in Paris. This unassuming building in a quiet cobblestone street, is where we meet him to about his youth, his work, and how Marie Claire changed his life.

You know, the ingredients of fashion photography are fashion itself, of course, so it's elegance. And at the same time beauty, women, the beauty of women, the relationships between women and fashion and clothing. It's this mix that is magical to me.

Paolo Roversi

You mentioned in your exhibition that the first commission from Marie Claire was very important to you, and that you "jumped for joy" when you received that call in 1977...

At that time, the legendary Claude Brouet was heading Marie Claire, one of the first fashion magazines I worked for. When I arrived in Paris in 1973, I had very few contacts. And the first significant series I did for Marie Claire is precisely the first one I made with the 20x25 Polaroid, you know, my large formats. I brought them to the editorial office, and they asked me where the prints were. I replied: that's all there is, I didn’t use film. They sent them to the printer, who sent them back them. I told them it was like a normal color print. "Just try!" Eventually, they were printed, and from then on, my Polaroids were accepted in the press. Marie Claire was the first one to go for it.

And you never went back to using film?

From then on, I only used Polaroids; it became my thing. At that time, photographers used them just for test shots, before taking the actual photo on film. Polaroids were used to try out lighting, framing, and settings. Magazines weren't accustomed to receiving them. But for me, when I saw what I could do with them, they became my end result. I didn't need film anymore; the Polaroid was the result itself. They’re like a daguerreotype or an autochrome: a unique print. I shot Polaroids for 30 years, a long period of large format. I started with color, and gradually transitioned to black and white. And ultimately I did both.

In 2008, Polaroid shut down production. How did you adapt your work to this change? Did digitalization accelerate your practice?

I still use long exposure, even in digital photography. When I work with a torch, the exposure is necessarily long because it happens in total darkness. The lens is completely open, but in the dark, nothing impresses the film. Then, as soon as I turn on my torch and illuminate part of my subject, that part is impressed. It's an old photographic technique, very simple, called light painting. I didn't invent it. Perhaps I'm the first to apply it to fashion photography. I like to think of photography as a black page on which I write with light. Music is written on a white page, drawings are traced on a white sheet, but photography is a black page that we mark with light. It's a job done in darkness. The inside of a camera is black, a darkroom is dark, as its name suggests... Black is essential to photography because light expresses itself in darkness.

And truly, there is a spectral quality to your photography...

Yes, photography for me is the art of nostalgia. I don't know how to say it differently: the presence of the past is the habit of the present. The past has disappeared, but it is present through photography. That is what fascinates me. There's a ghostly aspect when you look at a photo of someone. It's a fantasy that there's someone in front of us, a absent presence, a present absence. I really like this ambiguity.

Photography is a kind of alchemy. Being able to stop time, to create images, it's like magic.

Paolo Roversi

In the exhibition, it's very moving to see the very first photo you took at the age of 9, of your sister in her ball gown. Did you immediately know that you would be a photographer, that this would be your life?

No, not at all, at that time it was a game, something a bit magical. In fact, I never made that decision. I never said to myself: "Tomorrow I will be a photographer." It happened by chance, little by little, one thing after another. I was happy with what was happening to me, but it's not something I consciously decided. It just happened to me, that's all.

We are in your studio, where you have brought all the biggest names in the fashion world. Tell us about this place?

One day, I wanted to turn my studio into the subject of my work. In fact, I made a book called "Studio." I wanted my everyday tools, these objects that constantly serve me for my work, to become the protagonists for once, to be the subjects of my photography. I wanted to shoot the camera, the lamp, the backdrop, the little stools as I would have portrayed a girl, a boy, or a piece of clothing.

You are very respectful of women, and you like to work with the same women over and over again. Have some of them become your friends?

Yes, when I get along with a model, it creates what I like to call a photographic friendship. It's a mutual trust that develops, a type of friendship, and I enjoy renewing sessions with that person because it makes working easier, deeper. Everything flows. It allows me to go further in the images and in the photographic relationship. For me, the model is above all a human being, with her personality, character, and humanity that all touch me deeply. I seek their mystery, I try to unveil it, but not entirely, just lift a corner of that veil, because I like it to stay rather mysterious.

You have worked with the greatest designers of their time, including the avant-garde Japanese designers, whose work you have been able to show in an almost historical way. What struck you about working with them?

Rei Kawakubo is a blend of Japanese and Western culture – in her work, she embodies both Eastern and Western influences. So it's easy to play with these different and almost radically opposed interpretations. I've always had a lot of admiration for her, a lot of respect for her clothes. And she has always trusted me, she always appreciated my way of photographing her creations. I’ve had a beautiful relationship with the couturiers. For a fashion photographer, it's very important to have this relationship. I was lucky enough to work closely with the couturiers, and to create together a certain woman, a certain mood. Can you imagine that sometimes I had in my studio Azzedine Alaïa, dressing the girls himself, or John Galliano, doing the styling himself? I always say that it’s like being a pianist playing a concerto by Mozart, and having Mozart himself turning the pages of the score. It's an incredible, sublime opportunity.

With my camera, I have a relationship of love, truly love, there is no other word. Without my camera, I am nothing, none of this exists. I could not exist without my camera. It's a deep, essential relationship.

Paolo Roversi

Who are your masters? Your main photographic influences?

Nadar mostly. In fact, I'd say all the great portraitists. Diane Arbus, who is also, for me, a great portraitist.

What is your view on contemporary photography? Do new photographers also influence you?

I look at it less than the great masters, to be honest. There are young photographers who I find very interesting and who stimulate me in my work almost as much as the masters of the past. What I don't like, what bothers me terribly, is the great pollution of images that exists currently. Images that serve no purpose, that are made without reason, without love, without joy. I find all of that too much.

Moving back to your youth, has growing up in Ravenna influenced your work?

I'm not sure. I grew up next to the sarcophagi of emperors, the mosaics of Galla Placidia... It inevitably influenced my iconography, my imagination, even if not directly. These are resonances that come back inevitably in my work, whether I want it or not, in my colors, my chiaroscuro. I like to tell that as a child, when I played soccer, we drew the goalposts in chalk on Byzantine walls. All of this is in my subconscious.

The Paolo Roversi exhibition at the Palais Galliera will run from 16th of March - 14th of July 2024. Tickets are available here.