Mark Rothko at Fondation Louis Vuitton

Here's our review of the latest must-see exhibition everyone is heading to Paris for.

I'm in a large gallery space. The lights are dimmed. On the walls are large canvases exuding waves of colour as if they had their own internal light source. Many have benches in front of them, inviting contemplation. This is how Mark Rothko wanted his work to be seen. The Fondation Louis Vuitton and Rothko’s son Christopher have brought together one of the most comprehensive retrospectives of the inventor of slow painting and master of abstraction. If you’re looking for the profound, start here.

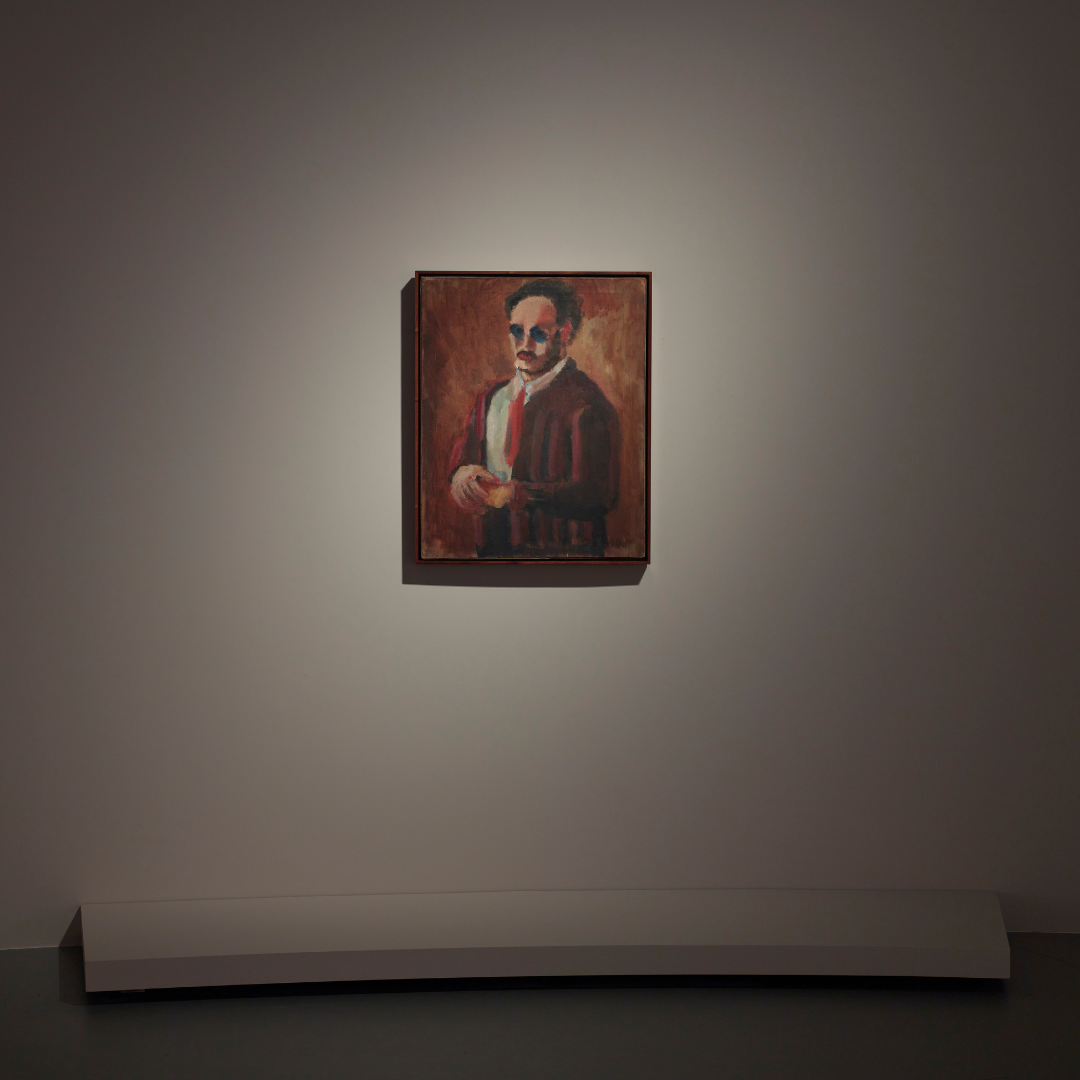

Rothko was born Marcus Rotkovitch in what is now Latvia in 1903. His Jewish family emigrated to Portland when he was 10, escaping the violent pogroms in Russia. He excelled in school, studied at Yale and settled in New York City. Here he became an artist. The Louis Vuitton show brings together his early figurative works from the 1930s. Moody smaller paintings of melancholic New York subways and urban crowds, alongside a rare self-portrait of the artist in glasses. Rothko himself was always frustrated by his “mutilation” of figures and moved towards the surreal and mythology during the war.

In the late 1940s, however, he began created the style he is so known for. Oversized canvases that seem to dominate over the viewer. Swathes of intense colour that can be overwhelming to stand in front of. Although his earlier abstract pieces collected here are of warm, pleasurable orange, yellow and pinks they are not light hearted. In fact, even here begins Rothko’s deep sense of trauma and horror of humanity. He later noted, “I would like to say to those who think of my picture as serene… that I have imprisoned the most utter violence in every inch of their surface.”

The exhibition is chronological and we see in the 1950s Rothko establish the compositional structure he is so known for. Two or three loosely rectangular shapes filling the canvas horizontally in strips. On closer look these shapes are muted, fuzzy at the edge, magical, unclear. Yet together in a painting they form something immense. Yellow against a dirty white. Black against a blue. It makes sense that Rothko saw his work in contrast to the immensity of music by Mozart. (One of the highlights of the show is a vitrine containing some of his book and record collection – cue Satre’s Nausea and Mozart’s The Magic Flute.)

Rothko resisted referring to his work as abstract, as a reduction. “My art is not abstract, it lives and breathes.” His main concern was not in fact colour, but a search for light. Like photography, the medium that dominated the 20th century, Rothko’s paintings transform light into image. His paintings are like dark spectrums, refracting colour but increasingly with a sense of deep heaviness.

The works become more bloody. Black on wine. Blood red on deep purple. Increasingly the difference between colours is so intense the viewer wants to throw themselves into the canvas like vertigo. The main transition visually occurs with the Seagram Murals. Originally a commission for a Mies van der Rohe skyscraper, the arts cancelled the contract and nine of these monumental works went to London’s Tate. They are hung here - as they normally are in the Tate Modern - exactly as the artist intended. The room is dark. The paintings like monoliths. The compositions echo windows in a blackened cathedral or prison. This is what existential emotion looks like.

By the late 1960s all colour has been removed from the work. We are left with shades of grey, black and deep navy. Almost monochrome, here the canvas is split into two halves – grey and an abyss of black. His take on the minimalism that had become so fashionable at the time. They resemble the surface of the moon. A surface without the human. A void. The Fondation chose to place standing Giacometti figurative sculptures in the room alongside this tombstone-like finality. Rothko committed suicide in 1970 at the age of 66, following years of ill health and depression.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Despite the weight of this final room, this exhibition is still one of the most inspiring, beautiful shows you made see in your life. A rare chance to see the breadth of the artist’s work. To experience art at its most philosophical, emotional and profound.

The exhibition is on till February 2024 so book now.

Writer and curator Francesca Gavin is Editor-in-Chief of EPOCH (@epoch.review), has a monthly show on art and music @nts.live called Rough Version, and is the author of ten books on contemporary art and culture. She has curated exhibitions at Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Fundação de Serralves (Porto) and Somerset House (London) and writes about visual art for publications including Financial Times HTSI, Beauty Papers, Twin and Frieze. @roughversion