The spring reading list—the page-turners that will have you hooked

Featuring truly fine debuts and household names

Welcome to spring. And with it, your new spring reading list – which sees a welcome return from some brilliant favourites (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Natasha Brown among them), alongside a handful of truly fine debuts and other gems.

We have a prize-winning short story collection, a sharp, dark, funny look at London’s rental crisis, a One Day-style love letter to the noughties music scene and the first in a startling new (to English language readers) literary series that pushes that well-worn trope, the timeloop, into bold – even profound – new territory. And that’s only the start. So settle in – it’s going to be a thrilling ride.

The Americanah author returns with her first novel in 10 years. Opening into March 2020 just after the first wave of global lockdowns have been announced, this is not, many will be pleased to know, a pandemic novel as such. Rather, Adichie uses the isolation and strangeness of that time as a framing device for lead character Chiamaka – a wealthy Nigerian-born travel writer who is based in the US – to look back on her life and relationships and ponder (in every sense) where next. Its rich, multistranded tale is broken into four main voices: Chiamaka, her best friend, the housemaid she sees as ‘family’, and her closest cousin. Each one builds on the last, opening out the narrative and offering differing perspectives and insights into the women’s relationships and ambitions, turning hot-topic issues around motherhood, race, gender politics, FGM and sexual assault into profoundly moving personal insights. In short, Dream Count lives up to both the anticipation and hype.

A collection of 30 short stories – some just a single page long – from the winner of the Merky Books New Writers Prize. Radojevic is a poet and women’s rights activist and her ear for both the rhythm of language and the causes and frustrations that shape our times are present and correct in what is a funny, playful, irreverent – but always sharply on point –examination of contemporary women’s lives. Subjects range from bodily autonomy to the price many women pay to navigate a so-called smoother path through life (‘She was born fierce, with a pair of wings, but somewhere along the way she sold them,’ Radojevic writes of her unnamed universal ‘girl’ in Blood Ridden). But there’s plenty of joy being celebrated in here too: in friendship, self-discovery and the pleasures of falling deeply, genuinely, in love.

A queer young writer who has so far failed to live up to his early creative potential (‘The world is at your feet, they said,’ he notes at one point. ‘I stamped all over it.’) is working a short-term contract as a creative writing tutor when he meets – and falls for – ‘the poet’. The poet is older, highly esteemed – and a woman. While in theory, that should be able to be accommodated in the open relationship he shares with his handsome live-in boyfriend, Michael, their burgeoning friendship-slash-relationship threatens to undermine every part of all their lives. Throw in a homophobic mother and hidden family secrets and you could, on paper, have a recipe for something that’s more salacious than sensitive, but Kelly is far too nuanced for that, crafting a tenderly written meditation on art, love and life that’s as much about the search for self as for connection.

Lanagan’s razor-sharp debut introduces twentysomething couple Aine and Tom as they prepare to move in together – a decision made as much from economic practicality as one of relationship intent. They find a suspiciously cheap (though still barely affordable) flat in a pocket of the city with a 24-hour organic supermarket on the corner, but no decent transport links. Once they move in, however, things begin to change. A mysterious mould blooms from the basement, threatening Aine’s physical health, while an even more mysterious neighbour – the old man who lives in the flat upstairs – does the same to her increasingly fragile mental state. Are we witnessing a ghost story or just another tale of the very real nightmare that is London’s rental culture? Lanagan’s genius rests in her ability to keep both narrative balls very much in the air throughout – with plenty of dark laughs along the way.

Brown’s debut, Assembly, heralded her as one of the brightest in Britain’s then emerging crop of young writers. This, her follow-up, sees the author pushing the spare, tight narrative style of her debut in different directions. It opens with what’s quickly revealed to be a long form online article about a gold bar that was stolen from a Yorkshire farm that was squatted and shut down after hosting an illegal rave during lockdown. Penned by Hannah, a previously struggling freelance book reviewer, it became a viral sensation, securing a Netflix deal that allowed Hannah to hook a big toe onto the lowest rungs of London’s property market. But as the novel progresses and different characters move to the forefront – shock journalist Lenny and banker Richard among them – it becomes clear that things as reported by Hannah are considerably murkier than they first appear. If Brown’s satirical brush is a little broad at times, Universality remains a smart, thought-provoking and pacy read about class, capital (cultural and financial) and the general state of divided Britain today.

We meet Tara on 18 November in the house of one Tomas Selter. Tomas, we learn, is Tara’s partner and she’s here, hiding from him in her own house, aware of every sound and move he’ll make before he makes it, because time, she tells us ‘has fallen apart’. She was visiting Paris on business when she woke up and experienced the same day for the first time 121 days before and has been caught in a timeloop ever since. Intriguingly, she’s not entirely stuck on repeat: a burn to her hand goes through stages from infection to healing; she is able to travel home to Tomas in rural France – but many other things are lost. Including Tomas’s memory, which resets each day.

As first the weeks, then the months, rack up, Tara’s hope of finding a way into the next day wears increasingly thin. But even as her plight deepens, she finds ever more to discover in the endless repetitive shape of a day lived again and again. And it’s through this exploration that Balle transcends the classic Groundhog Day conceit to create a narrative that explores much bigger and wiser themes about what it is, in every way, to be human – and keeps it gripping throughout.

In Balle’s native Denmark, On the Calculation… has become a literary sensation, with five volumes (out of an intended seven) in the series published so far. Only Volume I and II have been published in English so far – the first of which has, deservedly, earned the author and its translator Barbara J Haveland a spot on this year’s International Booker longlist. Is it too soon to ask for more?

One Day meets High Fidelity in Brickley’s sparky debut – two rather fittingly vintage references for a Noughties-set novel about music-obsessed wannabe writer Percy and budding musician Joe. We follow the will-they-won’t-they push and pull of their relationship from their musical meet cute at college (the pair bond over, of all things, a Hall & Oates song, which might be a litmus test too far...) and across the first two decades of the new millennium. While their relationship – professional and personal – flounders as Joe becomes a bone fide rock star, the question of the pair’s attraction for one another, it’s no spoiler to say, is never really in doubt. Rather, it’s in the narrative ‘deep cut’ – which follows Percy’s long and winding route to finding herself and discovering her talents – that the story really sings.

Eloise and Lewis set off on a two-week journey through the American Southwest that’s part work (Eloise is an academic studying drying of the Colorado River; Lewis works for an art foundation that’s funding an epic piece of land art buried deep in the desert), part Great American Road Trip. The couple are young and in love but as the journey continues, the pair become increasingly emotionally isolated from each other. Lewis is grieving the death of his mother, Australian ex-pat Eloise is dealing with the question of whether she may or may not be pregnant. As the name suggests, this was never a journey that was going to end well. It’s a credit to Watts’ skills as a writer that she’s able to foreshadow that so plausibly, while still keeping us guessing as to just what exactly the end – and its cost – will be. Tender and hauntingly sad.

Herman Mellville's Moby Dick tends to poll highly in those polls of the classic novels people haven't actually read. Guo’s infinitively enjoyable (and thoroughly readable) retelling is unlikely to suffer a similar fate. We’re in Victorian England when we first meet the Ishmaelle of the title who, orphaned and grieving the loss of her infant sister, binds her breasts and cuts off her hair to pass as a boy before heading off for a life on the high seas – eventually joining the whaling boat, Nimrod.

Guo’s retelling, however, is not simply a gender-swap, but a cultural one, too. In her version, Nimrod’s captain, Seneca, is a Black man of mixed heritage, and his obsessive hunt for the great white whale that drives him to the brink of madness is riven with racial trauma. It’s a propulsive, powerhouse of a read that doesn’t just stand on its own literary feet, it does so with such skill and verve that it might – just might – have you turning to its source material in a new light.

Nine months pregnant, Annie is ‘milling in the crib section’ at IKEA in Portland, fretting about the state of her finances, her career and her marriage when, seemingly out of nowhere, a monumental earthquake (the ‘Big One’) hits. She makes it out of the store alive with only one mission – to find her way to husband Dom. Over the course of the day that follows, Annie narrates their story to their unborn baby, Bean, charting the path of their life together. We witness their shift from hopeful young artists (Annie was an aspiring playwright, Dom still aspires to become an actor) to disillusioned thirtysomethings struggling to make the even basic building blocks of modern American life work and, in the process, Annie re-evaluates the ways to live a life. Pattee, a climate journalist by day knows of what she speaks – Portland lies smack bang in the heart of the very real Cascadia fault line, which has been estimated as having a one-in-three chance of triggering the Big One in the next 40 years – and she doesn’t shy from the horror of such a devastating event. In Annie, however, she’s able to render it funny, tender and hopeful, as well as frightening.

Nobel laureate Gurnah’s first novel since he was awarded that very prestigious gong in 2021, is a multigenerational coming-of-age saga set in postcolonial Zanzibar and Tanzania that follows three characters from three very different backgrounds across several pivotal decades in both their own lives, and that of their country. Left to live with his grandparents after his mother flees her forced marriage to a much older man, young Karim is determined he will do better. Early on, his fate is twinned with that of Badar, who moves into the household as a young servant boy. But as Karim’s star rises – he attends university, meets and marries his wife, Fauzia, the third major cog in this narrative wheel – Badar’s is thrown into disarray by an accusation that sets off a chain of events that, in time, changes all their lives irrevocably .

In many ways, Szalay's charting of one man’s life from his youth in Hungary to adulthood in London and beyond serves as a sort of companion piece to his exceptional 2016 Booker-shortlisted novel-in-stories All That Man Is. Like that novel, it’s revealed in a series of interlinked stories, but the focus on a single character, István – who we first meet as a teenager in small-town Hungary heightens the sense of dislocation that has become something of a hallmark for Szalay. István is someone who moves through life as if it’s something that happens to him, rather than a person with any real agency. However shocking the things he encounters – and he encounters a lot, from sexual abuse and prison time to witnessing a friend die in his arms while serving in the Middle East – István soldiers on. He moves to London where his fortunes – largely guided by the whims and actions of others – continue to rise and fall until a single spectacular act on István’s part lights the fuse that will blow his world apart.

Harman’s voice-driven debut is a fun, pacey, comedy-thriller in which ex-girlband singer and single-mom Flo will do anything – anything – to protect her beloved son 10-year-old Dylan. When one of his classmates – the heir to a fast-food empire and ‘little shit’ who has been terrorising Dylan at the posh west London school he attends – suddenly and mysteriously disappears, that anything extends to doing whatever she can to prove her son is not responsible, despite growing evidence to the contrary. All while trying to kickstart her dead-in-the-water singing career and fend off the threat of local serial killer, the Shepherd’s Bush Strangler. Enlisting the help of fellow expat Jenny, a lawyer whose no-nonsense approach serves as a great foil to Flo’s flakiness, she sets out to crack the case. As an American-in-(West) London herself, Harman has a great outsider’s eye for the various hierarchies and snobberies of the capital’s postcodes and class system. Very, very funny.

Museum archivist Sara Hussein is returning home to LA from London when she’s taken aside for questioning by security. We’re in a near-future US in which data from a sleep device designed to relieve insomnia, monitors your dreams and flags any propensity to commit future crimes to the state and Sara’s dreams suggest she wants to do physical harm to her husband. She’s transferred to the Dream Hotel of the title for further monitoring and – like the Hotel California – once you’re in, it’s pretty much impossible to leave. Newly longlisted for this year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, Lalami’s propulsive fifth novel is proof that the trend for dystopian fiction isn’t going anywhere.

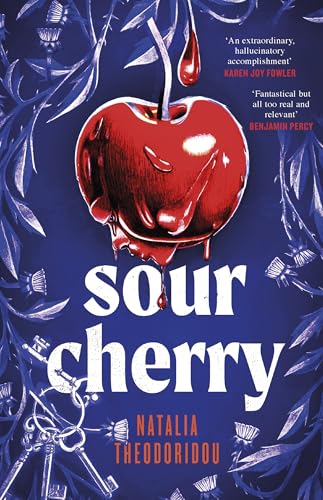

Are monsters born or made? That’s one of the central questions underpinning Theodoridou’s dark, bloody retelling of Bluebeard – the story of the French nobleman and who killed his wives for disobeying a so-called simple trust exercise and kept their bloodied bodies in the basement of his castle for the next wife to discover and, in due course, meet a similar fate. As that suggests, this is not a light read. It is beautifully, poetically written. Rich, dense – and just a little relentless – this is one for fans of the new generation of dark, feminist body horror.

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Catherine is a freelance writer, editor and copywriter. As a freelance journalist, she wrote for titles including The Times, The Guardian and The Observer before spending eight years as commercial editor for Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire and Elle Decoration.

Books, art and culture of all stripes are a particular passion. Since returning to freelance in 2019, she has turned her skills to branding and full-service content creation for a broad range of luxury, arts and lifestyle brands, alongside more creative projects, such as book- and script-editing.

-

Style Briefing: Matthieu Blazy's last hurrah at Bottega Veneta

Style Briefing: Matthieu Blazy's last hurrah at Bottega VenetaHow the designer delivered a fresh perspective while also honouring its history of craft and creativity

By Rebecca Jane Hill

-

The Emily in Paris cast has spoken out as one of its stars officially quits the show

The Emily in Paris cast has spoken out as one of its stars officially quits the showBy Jenny Proudfoot

-

Timothée Chalamet’s mother has opened up about his relationship with Kylie Jenner

Timothée Chalamet’s mother has opened up about his relationship with Kylie JennerBy Jenny Proudfoot