The latest internet comments about Margot Robbie highlight how societally normalised incel culture is

Plus, how online incel hatred translates into real-life crimes.

By now, you'll have likely seen hundreds of photos of Margot Robbie doing the rounds on your social media feeds. The actor, producer, and women's rights activist is playing Barbie in the fiercely-anticipated remake, due to hit cinemas this Friday.

So why, then, amidst the excitement, have some men taken to Twitter to label Robbie "mid" online?

A bit of background for you, first, if you're not sure what "mid" even means. According to Urban Dictionary, the term is slang for something or someone that's below average or low quality.

Where did the trolling start? One Twitter user took it upon themselves to share a photo of Robbie without makeup with the caption: “This is her without makeup. Definitely mid." Another replied: “She is a hard 7. You used to find a Margot Robbie in every Blockbuster Video in 1995." The post has since gone viral.

Baffled by how Robbie, an actress cast to play the archetype of a "pretty" woman, could possibly be called average? Us too. And herein lies the problem. This debate isn't about Robbie's looks: rather, it's a classic example of everyday misogyny and men trying to reclaim status or power by putting women down.

The new Greta Gerwig Barbie flips what we once knew of the iconic doll on its head - this time around, we're provided with a feminist take on her story, free from the male gaze. In the adverts alone, you can see various versions of Barbie - President Barbie, lawyer Barbie, diplomat Barbie, and more, while Ken is - well, he's just Ken.

Here, Laura Bates explains more about the vast global network of men purporting extreme misogyny and opposition to feminism. Operating in websites, blogs, and online forums - in this case, on Twitter to drag Robbie down - their women-hating ideologies lead to shocking offline consequences. While we don't know that the men trolling Robbie were, in fact, incels, the behaviour is a worrying trend that could be risking everyday safety. Keep scrolling to explore how these communities can lead to terrifying behaviour offline, too.

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

How Margot Robbie being labelled "mid" highlights how societally normalised misogyny is

What is an incel?

First things first - an explainer for you. Incels (Involuntary Celibates) are men who aren’t having sex but would like to be, and they blame women for that. They believe that women owe them sex and actively incite violence against them. They suggest that women should be kept as sex slaves and stripped of their rights, and repeatedly revere and canonise men who have committed massacres of women.

They encourage each other to rise up in what they call the Day of Retribution, when men will go offline and slaughter as many women, as they can, to punish them. Men who have committed real life massacres explicitly in the name of this particular movement include Elliot Rodger and Alek Minassian. But there are also examples close to home like Ben Moynihan, a teenager who went on an attempted murder spree in the UK, leaving notes for police about how he despised all women because they didn’t have sex with him.

Why isn't misogynistic extremism being taken seriously?

I think there are a number of reasons. The first is that it’s a relatively emerging threat in terms of mass killings, so people are failing to join the dots and make the connections between them.

But I think a big part of it is that misogyny is so normalised in our society that we really struggle to recognise this as something extreme. We are so used to women being murdered by men. One woman is killed on average every three days by a male current or former partner in the UK - that is literally the backdrop to our daily life. So I think we struggle to see these as atrocities and it is a huge blind spot. It’s also because of who often commits these offences - educated white men and so the criminal justice system finds excuses for them.

The way in which we collectively excuse, condone, normalise and ignore these white men when they commit mass shootings and terror atrocities really hampers us as a society in tackling the problem.

I was aware of these communities because as a woman writing on the internet about feminist issues, these men come to you. So I have been aware of them for some time, but there was an argument in feminist circles that we shouldn’t give them the oxygen of publicity and that was something that I largely agreed with. So, for a long time it just wasn’t something that I really spoke about publicly.

What changed my mind was the recognition that these groups actually have a lot of offline power. We’re talking about a very established network here with millions of views and followers, with hundreds of thousands of members. They were doing pretty well without the oxygen of our publicity and they were beginning to commit an increasing number of terrorist attacks.

The Toronto van attack, the massacre of a woman with a machete in a Toronto massage parlour, and another attack in Canada where a man attacked a woman and her young daughter in a pram in the parking lot of a store. The fact that these men were actually increasingly killing in the name of this extremism meant that it was no longer something that could be ignored. But also, there was for me a particular tipping point in the sudden realisation that they were radicalising and grooming school boys in a mass campaign without anybody noticing.

How important is having conversations to ensuring progress?

Very. We can’t tackle a problem if people don’t know the problem exists. That was why I started the Everyday Sexism Project. People said that sexism didn’t exist anymore and that women were equal and I realised that we can’t begin to encourage people to be part of solving a problem if they honestly don’t believe it’s there in the first place.

That’s how I feel about this as well. We can’t mobilise people to protect youngsters who might be radicalised and support women who might be victims if they have no idea that these communities even exist. It’s really important that we talk about it and it’s crucial for young men in particular that we have open conversations for the sake of their mental health.

How do these groups prey on vulnerability?

The really tragic thing is that many of the young men who are driven to these websites are suffering. They are suffering from the traditionally prescribed societal strictures of masculinity and what it means to perform that. The irony is that male mental health as a crisis needs to be tackled, something that the manosphere would claim to believe is very important, but actually, it suits them for men to continue suffering.

They continue to tell men, ‘You have be powerful, violent and in control of your woman - that’s the only way for a man to be successful’. They really double down on exactly the kind of messaging that is harming men in the first place. And if we could provide boys with offline spaces to explore some of the anxieties, fears and frustrations that often send them into the arms of these communities, then that would be a really good way to offset their power.

It can’t be a coincidence that these communities have risen so sharply in their influence and success at grooming young people at the same time that we’ve seen a massive decline in funding for youth services. Hundreds of youth centres have been forced to shut their doors and boys don’t have that same opportunity offline to create a sense of community, purpose, belonging and brotherhood. That’s what these communities are offering them.

Why isn't there more conversation around these issues?

It’s a very difficult thing for people in the real world to understand. It sounds completely bonkers to some people when you say that because of your job you hear from 200 men a day about how they would like to rape and disembowel you. Most people just don’t know how to respond to that and will usually say ‘Oh but it’s not real’ or ‘they don’t really mean it’. There’s an empathy gap.

If someone said, ‘I just watched a scary movie and when I woke up in the night I felt really scared’, we’d all go ‘Yeah, I get that’. But for some reason, if a woman says, ‘I read ten men fantasising about disembowelling me yesterday and then I couldn’t sleep and felt sick all night’, people will go ‘They’re just trying to get to you, why are you letting them?’.

One men’s rights activist in the States was bringing a lawsuit about a draft being sexist to men. He wasn’t happy with the judge who was presiding over the lawsuit (he perceived him to be a feminist), so he turned up at her house disguised as a delivery driver and opened fire, shooting her son dead and seriously injuring her husband. These actually are men who do go offline and kill women. It only takes one of them, so we have every right to be scared.

Men Who Hate Women, by Laura Bates, published by Simon & Schuster, is available in paperback at £9.99.

Ally Head is Marie Claire UK's Senior Health and Sustainability Editor, nine-time marathoner, and Boston Qualifying runner. Day-to-day, she heads up all strategy for her pillars, working across commissioning, features, and e-commerce, reporting on the latest health updates, writing the must-read wellness content, and rounding up the genuinely sustainable and squat-proof gym leggings worth *adding to basket*. She also spearheads the brand's annual Women in Sport covers, interviewing and shooting the likes of Mary Earps, Millie Bright, Daryll Neita, and Lavaia Nielsen. She's won a BSME for her sustainability work, regularly hosts panels and presents for events like the Sustainability Awards, and is a stickler for a strong stat, too, seeing over nine million total impressions on the January 2023 Wellness Issue she oversaw. Follow Ally on Instagram for more or get in touch.

-

This perfume was created in 1892, and I wear it today—it’s musky, sexy and deserves a spot in your collection

This perfume was created in 1892, and I wear it today—it’s musky, sexy and deserves a spot in your collectionIt smells nearly identical, 153 years later

By Nessa Humayun

-

Butter yellow is the colour of the season—and experts have confirmed it looks chic on nails too

Butter yellow is the colour of the season—and experts have confirmed it looks chic on nails tooHere's how to choose the best shade for you

By Mica Ricketts

-

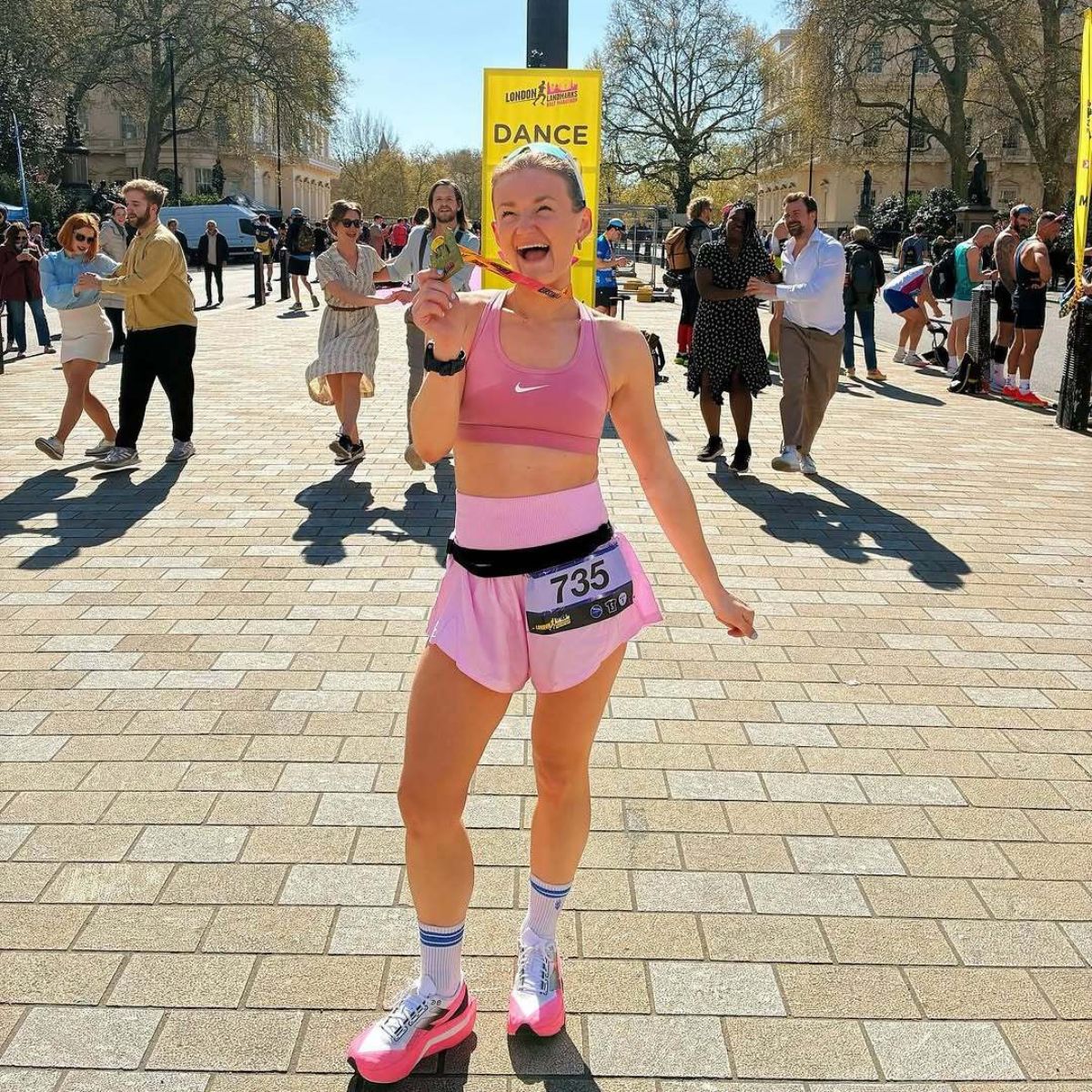

Pink activewear is officially the must-wear trend of the season - 9 items our Health Editors can't stop wearing

Pink activewear is officially the must-wear trend of the season - 9 items our Health Editors can't stop wearingMake your workout even more fun with a pop of pink.

By Amelia Yeomans